On January 3rd, the Venezuelan leader Nicolas Maduro was removed by US special forces as leader of the South American country. The reasons and political consequences of such a move merit a separate article in a very different publication, but as a Venezuelan geodesist, today I would like to explore the future implications for our profession. As a young professional I was very familiar with the mapping agency in Venezuela, and I had the opportunity and the privilege to use their resources (primarily the location and coordinates of second-degree control points) and the basic cartography of the country. In those days, late 70’s and early 80’s, the agency’s morale was high, it was well equipped, professionally managed and had a clear mandate and official support from the democratically-elected Executive branch. What has happened over the past 40 years is nothing short of an expertise catastrophe.

For most countries, a national map is more than a reference sheet or a colorful wall poster. It is the foundational layer upon which infrastructure is designed, land is administered, resources are managed, and environmental risks are understood. It is the quiet, invisible architecture beneath every road, pipeline, dam, and cadastral record. In Venezuela, however, that foundation has been eroding for decades. The country’s official maps, once the pride of a technically competent national cartographic agency, have become relics of a bygone era.

To understand the scale of the problem, one must begin with the institution at the center of it: the national mapping authority. For most of the 20th century, this was the Dirección de Cartografía Nacional (DCN), a technically rigorous agency that produced the country’s topographic series, maintained its geodetic network, and served as the authoritative source of geographic information. In the early 2000s, the Chávez government reorganized it into the Instituto Geográfico de Venezuela Simón Bolívar (IGVSB), a change that was more than cosmetic, even though some of its leaders tried very hard to keep producing good mapping, the administration did not help. Over time, the institution’s technical capacity, funding, and independence eroded, and its output shifted from systematic national mapping to sporadic thematic products and politically motivated cartography.

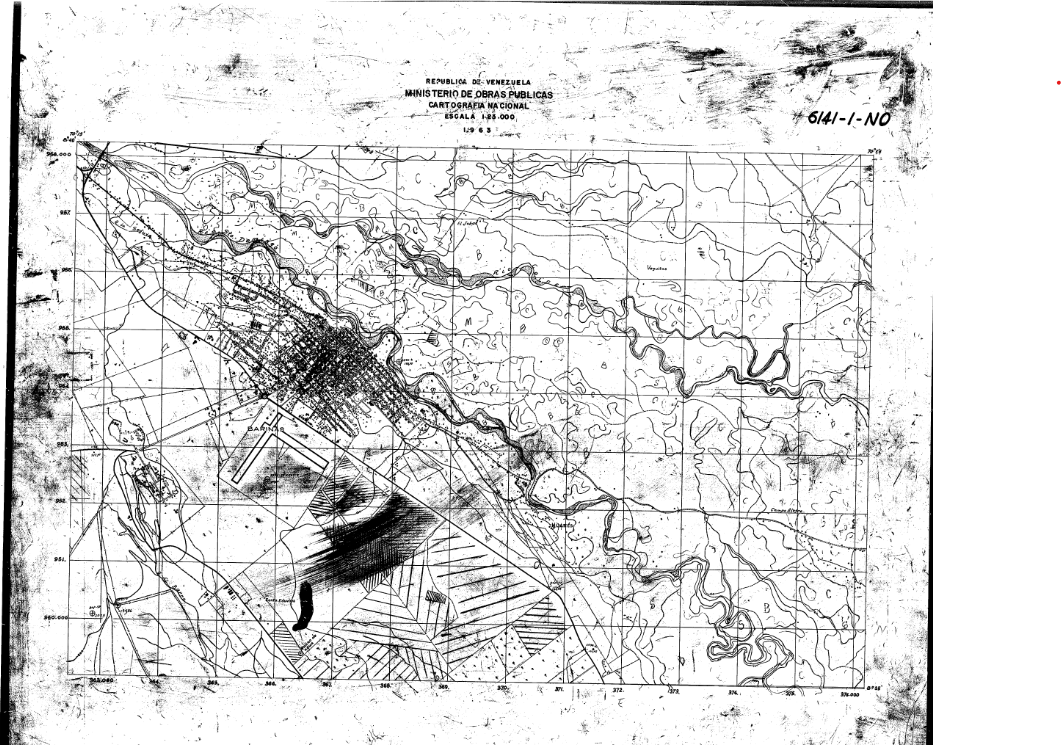

The result is stark: Venezuela has not conducted a nationwide topographic survey in more than 16 years. Between 2000 and 2015 just a few sporadic efforts such as Cartocentro, and REGVEN (the re-measuring of most control point using GPS). The country’s most detailed and authoritative maps, the 1:25,000 topographic sheets, were last updated between the 1980s and early 2000s. The 1:100,000 and 1:250,000 series are even older, with many sheets dating back to the 1960s through the early 1990s. These maps were produced before GPS became ubiquitous, before SIRGAS became the regional geodetic standard, and before modern photogrammetry and digital elevation models transformed the discipline.

The consequences of this stagnation ripple across every sector. In 1999 the IGVSB adopted the SIRGAS-REGVEN datum, a geocentric, non-conventional reference system, compatible with the rest of Latin America, but not all maps were converted or adapted, leaving the horizontal accuracy of legacy maps tied to the outdated PSAD56 datum, with errors that often deviate between 20 to 200. In the sparsely surveyed regions of Amazonas and the Guayana Shield, positional errors can exceed half a kilometer. Vertical accuracy is equally problematic: contour lines derived from mid‑century aerial photography or early radar surveys carry uncertainties of ±10 to 30 meters, making them unsuitable for hydrological modeling, floodplain delineation, or engineering design.

Coverage is uneven. Urban centers such as Caracas, Valencia, and Maracaibo have the best historical mapping, but even these areas have grown dramatically since the last official updates. Entire neighborhoods, industrial zones, and informal settlements simply do not exist in the official record. The status of maps in rural and frontier regions is far worse. Large swaths of the Orinoco Basin and the Amazonian south have only first‑edition sheets from decades ago, never revised, never validated, and never integrated into a modern geospatial framework.

Thematic mapping, land use, hydrology, natural resources, has continued sporadically, but without the backbone of updated topography or a modern geodetic reference frame. The most recent national land‑use maps date from 2015 and rely heavily on medium‑resolution satellite imagery. Hydrological layers are misaligned, incomplete, or outdated, with river networks that fail to reflect sedimentation, diversions, or mining impacts. Administrative boundaries are updated frequently for political reasons but often lack geodetic rigor or consistency.

Digital readiness is another critical weakness. Many official datasets exist only as scanned raster sheets or legacy vector files with incomplete metadata. Georeferencing is inconsistent. Interoperability with modern GIS systems is limited. There is no unified national spatial data infrastructure (NSDI), no authoritative web services, and no standardized metadata catalog. The IGVSB does not have the budgetary means to maintain the entire geodetic network, leveling, gravimetric or municipal, but there are certain documented efforts to update a few points in a SIRGAS‑aligned framework.

Apart from some collaboration projects with the national oil company PDVSA (Petroleos de Venezuela S.A.) to map specific oil-rich corridors in the eastern part of the country, very little new surveying has been done to keep the information current.

Perhaps the most consequential gap lies in the cadaster. Venezuela lacks a national, unified, digital, georeferenced cadastral system. Municipalities maintain their own records, often on paper, with inconsistent standards and no national integration. Parcel boundaries frequently fail to match ground reality, and datum inconsistencies introduce positional errors of tens or hundreds of meters. For investors, developers, or planners, this is a minefield: land tenure cannot be reliably verified, boundaries cannot be confidently located, and disputes cannot be resolved with geospatial evidence even with a physical land survey, due to inconsistencies in the reference system used.

Taken together, these deficiencies paint a clear picture: Venezuela’s national mapping system is obsolete, fragmented, and technically inadequate for modern development. The country’s maps are frozen in time, unable to support the demands of infrastructure planning, environmental management, resource development, or urban governance. Any serious national reconstruction effort, whether driven by public investment, private capital, or international cooperation, will require a comprehensive remapping of the entire country.

And that brings us to the second part of the story: what such a remapping effort would look like and an informal proposal on how to start.

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)