Dr. Jane Goodall’s groundbreaking research at Gombe National Park in Tanzania began in 1960, and transformed our understanding of chimpanzees and redefined the relationship between humans and animals. Dr. Goodall dedicated her life to conservation and community empowerment. Her recent passing marks the end of an extraordinary career in ethology and conservation science. Yet her legacy lives on powerfully through the Jane Goodall Institute and the countless individuals and communities she inspired worldwide. Her pioneering work revealed that chimpanzees make and use tools, have complex social structures, and possess individual personalities; discoveries that fundamentally challenged our understanding of what it means to be human, for the better.

Dr. Lilian Pintea, Vice President of Conservation Science for JGI, has worked alongside Dr. Jane Goodall since 2000, pioneering the application of remote sensing, GIS, lidar, and high-resolution satellite imagery to protect chimpanzees and their habitats across Africa. This year, Geo Week is honored to have Dr. Pintea deliver a keynote address at the 2026 Geo Week conference and for members of the JGI to have a presence at the conference.

The institute's current work embodies Dr. Goodall's profound philosophy: that humanity can only reach its full potential "when our clever brains and our compassionate hearts are connected."

This principle guides every aspect of JGI's conservation science strategy, from analyzing satellite data to providing local communities with the tools they need to strengthen their environment. Dr. Goodall's vision that conservation must be rooted in compassion, scientific rigor, and respect for local communities continues to shape the institute's innovative approach to using technology for conservation action.

As time has gone on, geospatial technologies have become increasingly indispensable to this mission, enabling JGI to monitor forest health in real-time, map critical chimpanzee habitats and migration corridors, and measure the tangible impact of community-led conservation initiatives. But perhaps most importantly, these technologies help the communities understand that the lives of people, animals and their shared environment are all interconnected.

Bridging the Research Gap

When Dr. Pintea joined JGI’s Center for Primate Studies at the University of Minnesota as a PhD student in 2000 and started to work with Dr. Goodall and JGI team in Tanzania, he brought specialized expertise in remote sensing and GIS to an organization renowned for its groundbreaking chimpanzee behavioral research. The JGI’s Gombe Stream Research Center had accumulated decades of meticulously handwritten notes documenting chimpanzee, baboon and other primate behaviors, but as Pintea observed, "no one was looking at mapping habitat change."

This represented a critical gap in understanding. To truly comprehend chimpanzee populations and their long-term viability, researchers needed to integrate behavioral data with habitat analysis, something that would require technology able to cover broader areas and reach areas difficult to access by researchers on the ground.

Pintea's early work involved constructing an unprecedented historical dataset of habitat change. The team digitized aerial photographs dating back to 1947 from archives in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and combined them with satellite data from Landsat MSS (beginning in 1972) and Landsat ETM+ (through 1999). This created a comprehensive, multi-decade record of environmental change.

The core objective was ambitious yet essential: "We started using satellite imagery to put both people land uses, ecosystem services and chimpanzee habitat changes on the same map and develop a common language to understand how they are interconnected," said Pintea. This common language would prove crucial for bridging the divide between conservation science and community needs.

The findings from this early geospatial analysis revealed a stark contrast. Inside Gombe National Park, the data showed habitat restoration, where tropical dry forest and woodland vegetation was returning, and fires, illegal logging, farming and other threats were being effectively controlled. Outside the park's boundaries, however, Pintea observed that "the natural forests and woodlands experienced drastic loss leading to degradation of both chimpanzee habitats and ecosystem services for people such as flood control and soil stabilization."

Satellite imagery provided critical insight into the drivers of this degradation. In the 1970s, people have been moved from scattered small settlements to larger established centralized villages, concentrating populations in ways that led to unsustainable resource use patterns. Decades later, combined with poverty and high population growth reaching in some years to 4.8 percent / year, the highest in Tanzania, the environmental consequences were clearly visible from space. It was clear that by the late 90thies deforestation, land degradation, and habitat fragmentation were spreading across the landscape.

The High-Resolution Revolution

In 2001, JGI became one of the first organizations to apply Ikonos 1-meter satellite imagery for chimpanzee research and community-led conservation in Africa, which was work that formed part of Dr. Pintea's dissertation. The impact of this high-resolution imagery cannot be overstated, said Pintea. It fundamentally transformed how researchers, conservation practitioners, government officials and communities perceived and developed a common understanding of the landscapes.

"Suddenly you could see every tree, every foot path. You can see houses... Wow, everything is now transparent," Pintea recalls. For local decision makers and conservation practitioners around the globe every village was now on the map and could be identified and represented thanks to the application of high-resolution technology.

The analytical power of this data was equally impressive. High-resolution 4-meter Ikonos multi-spectral data, used to derive canopy layers, proved to be "one of the most explanatory variables" in models analyzing chimpanzee hunting behavior according to Pintea’s work. This demonstrated that visibility defined by the detailed habitat structure directly influenced chimpanzee hunting behaviour and ecology in measurable ways.

For nearly 25 years, JGI has continued to find new ways to utilize satellite imagery and has developed partnerships with leading satellite imagery providers, including NASA/USGS, Space Imaging/ Digital Globe/Maxar/Vantor, Planet Labs, Umbra Space, and ICEYE utilizing data as part of JGI’s Science and Knowledge platform powered by Esri’s ArcGIS, AWS and other cloud technologies s to support their research and conservation work.

High-resolution imagery does more than reveal habitat loss. As Dr. Pintea explained, it can be used to identify specific drivers behind that loss, whether they are environmental or a result of human behavior. JGI's analysts can now distinguish between illegal mining operations, in some cases even under the dense tree canopies, logging concessions, subsistence and cash crop farming, unauthorized settlements, and charcoal production sites. This specificity provides both transparence and accountability to stakeholders, local decision makers and community members.

While initially trepidatious about showing villagers remote images of their homes and forests, the responses Dr. Pintea’s team received back in early 2000s were profound.

“A representative of a village government said to us, 'thank you for sharing these images - now we see that we are on the map, and the world cares about our village.'”

This recognition matters deeply. When communities can have a say and ensure that they are accurately represented in geospatial data, they gain agency in land use planning and resource management decisions. The imagery helps villagers make better decisions as they navigate the complex pressures of climate change, population growth, and land degradation.

In many parts of Africa, existing maps contain significant errors—village names are wrong or missing, roads are misplaced, and administrative boundaries are inaccurate. High-resolution satellite imagery provides communities with better, more current basemaps of their own lands.

"I've seen many times that when two satellite images, a before and after, are combined with a good story, decision makers actually would change their perceptions of the problem, leading to better solutions," Pintea explains. The objective nature of satellite imagery, combined with compelling visual storytelling, has proven to be a powerful catalyst for policy change and conservation action.

Unlocking the Potential of Lidar and 3D Mapping

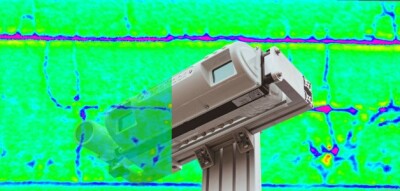

While JGI researchers recognize the transformative potential of lidar and drone technology, the organization has also confronted the practical challenges of cost and data processing. Nevertheless, they've forged ahead with innovative pilot projects.

In Uganda, JGI partnered with Restor, a global hub for nature restoration, to deploy drone-mounted lidar and handheld lidar systems, creating detailed 3D maps of conservation sites. These maps revealed tree density, canopy openness, and biomass with unprecedented precision.

One particularly promising application currently being explored is potentially using lidar to map chimpanzee nests. Traditional chimpanzee population field surveys are expensive, time-consuming, and logistically challenging. Lidar technology could potentially increase accuracy while reducing both cost and field time, representing a significant advancement over methods relying solely on optical natural color composite or multispectral imagery.

Breaking Down Data Silos with Generative AI

JGI is currently deploying a cutting-edge generative AI Gombe research platform developed in collaboration with Amazon Web Services. Dr. Pintea is particularly excited about AI's ability to "remove the silos between numerous data workflows and databases."

For decades, Gombe research data has been fragmented across different formats and data storage and management systems. Handwritten paper protocols and maps, digitized paper notes, videos, ecoacoustic recordings, satellite remote sensing and other data have all existed in separate silos. Generative AI can seamlessly integrate these diverse data streams across multiple databases, revealing connections that would otherwise remain hidden.

For example, AI analysis is helping researchers link species richness as detected from ecoacoustic devices to specific habitat characteristics derived from lidar and high-resolution satellite data, such as tree heights and canopy cover. These insights can inform more targeted habitat management and restoration efforts to protect biodiversity.

Technology with a Human Heart

As geospatial technology becomes increasingly sophisticated, JGI emphasizes the critical importance of keeping it human-centered. Dr. Pintea articulates this vision clearly: the geospatial community must ensure that innovative technology "be made to be more human-centered and therefore help the people as a tool and not necessarily replacing... or being applied against them."

"I see a huge challenge and opportunity in connecting global conservation discussions and goals with local realities and needs on the ground. The challenges of people in rural areas across the globe need to be heard .... Technologies, including satellite imagery, lidar, have a very important role to play in helping us see how people, animals and the environment are interconnected, village by village, while zooming out to have a common view of the world – like the iconic NASA "earthrise" photo did, shifting once again humanity’s perspective about how to work together to protect our fragile planet.

"Maybe [a villager] is not cutting down that tree to deliberately damage the environment, but because it is the only way that he can get some money to pay for medicine for his sick wife. I think the solution is for us to work together, guided by imagery and evidence and data, to make more effective and more compassionate solutions."

This philosophy encapsulates Dr. Goodall's original insight that “clever brains must work in harmony with compassionate hearts.” Geospatial technology provides transparency, objectivity, and accountability, but its ultimate value lies in facilitating communities as they protect the landscapes they share with local wildlife.

Dr. Jane Goodall's legacy endures not only in the scientific discoveries she made but in the movement she built, a global community committed to conservation, compassion, and hope. The next 25 years of geospatial conservation will undoubtedly bring new technologies and capabilities. If JGI's journey offers any lesson, it's that these tools will be most powerful when they serve not just to observe and analyze, but to strengthen and protect the communities at the frontlines of conservation action.