It has been several years since I have attended INTERGEO in person. Usually Matt Collins is the one to cover this massive geospatial expo, bringing us his highlights and insights from year to year. I returned this year not knowing what to expect on the floor. While there was a lot that didn’t surprise me at all, like the continued advances from big players like Leica, and bold moves from Topcon, there were a few booths and presentations that caught me by genuine surprise this year.

While a lot of the geospatial world focuses on large-scale terrestrial mapping, this year’s surprises highlighted significant advancements in bridging traditional technological domains and introducing entirely new hardware. The goal of this roundup is to highlight the most disruptive observations, specifically focusing on innovations that add unprecedented geometric accuracy to geospatial data and drastically reduce the size barriers for lidar technology.

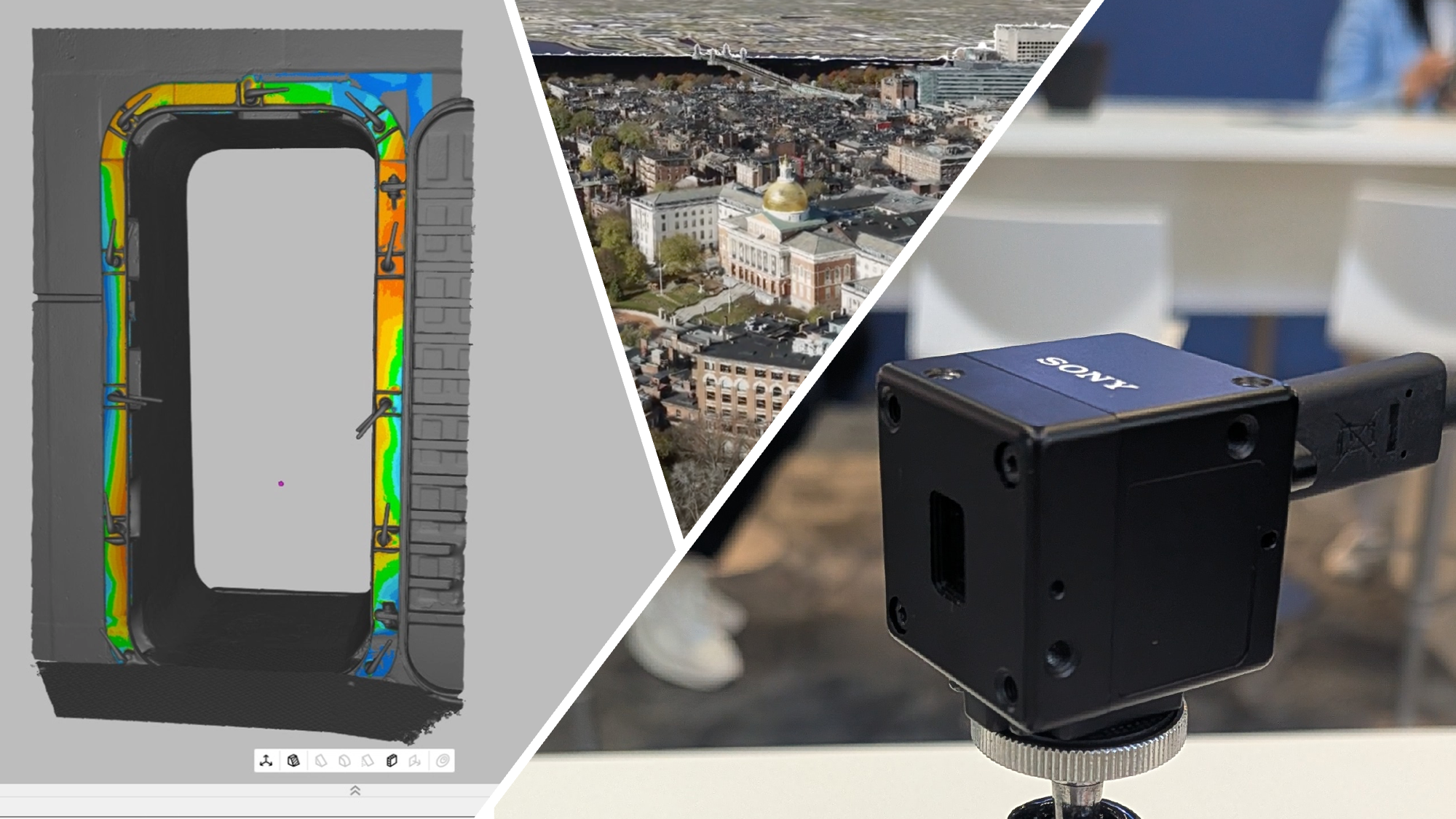

Structured Light Scanning + Lidar = Multi-resolution Meshes

Artec 3D is a Luxembourg-based company that designs and manufactures professional 3D scanning hardware and software. Their products span handheld and desktop scanners, laser and structured-light systems, and a suite of tools for processing, editing, and analyzing 3D models. I was surprised to be approached by Paul Hanaphy, Content and PR manager for Artec.

So what was a structured-light scanner manufacturer (typically working in the manufacturing and 3D printing space) doing at a geospatial show? The answer was fascinating.

Hanaphy talked to me about their idea to bridge the gap between metrology-grade accuracy (e.g., from the structured light scanners) and large-scale geospatial mapping by fusing data from two typically separate technologies. They have started blending data from their large-scale lidar scanner (the Artec Ray 2, a scanner developed with Leica Geosystems) with high-resolution handheld structured light scanners (like Leo or Spider 2).

Handheld scanners utilize structured light and blue light scanning, projecting black patterns onto an object to capture texture and geometry. These devices offer extremely high accuracy, such as Leo being up to 0.1 mm accurate, and Spider 2 achieving up to 50 micron (0.05 mm) accuracy. This accuracy level is close to metrology-grade, surpassing typical geospatial accuracy metrics. Artec Studio software allows users to combine these coarse lidar point clouds with detailed up-close scans. The software can then fuse the data into a high-resolution mesh, automatically using the most detailed data available.

Why It's Surprising: Imagine scanning a complex piece of industrial equipment but also having to cover a large warehouse area in which it is located. By blending these two types of scans, you can get a large overview of the space combined with the detail in only the places where that detail is needed. This could have implications for infrastructure inspection, factory planning or capturing cultural heritage. Imagine an entire church being scanned with lidar and then statues and other historical objects being captured with higher fidelity and accuracy.

Lilliputian Lidar

Walking through the hall, I stopped by Sony’s booth to talk to them a little bit about their done sensors, but something caught my eye that was a black square about the size of a golf ball. It turns out, that tiny package contained a prototype direct Time of Flight lidar that they describe as a “completely new technology” called the AS-DT1. It utilizes a Single Photon Avalanche Diode (SPAD) to amplify the smallest returning light internally to detect a surface. This allows the sensor to detect surfaces that are typically challenging, such as black objects, which normally do not shine light back. It employs a laser and an array sensing mechanism.

The most striking feature of the device is its minuscule form factor. The product specifications list the sensor's dimensions as 2.9 cm (1.14 in) W x 2.9 cm (1.14 in) H x 3.1 cm (1.22 in) D. When presented as a prototype at the show, it was noted to weigh only 42 grams. If the housing were removed entirely, the weight would drop to just 14 grams. This extreme minimization means the device's form factor alone is considered a "whole other game changer," allowing it to be implemented in many new places. Its small size and weight make it "ideal for applications with space and weight constraints, including drones, robotics and more".

While I got the distinct impression that this was a prototype that came out of true curiosity and aimed at platform manufacturers, there are some potentially disruptive applications for it, considering its accuracy and tiny form factor. Obviously, in weight-restricted applications like UAVs, and the ability to generate a point cloud and straight distance measurement without adding weight could be applied in may different ways. Robotics could take them on as navigation aids or other measurement assistance, but with less of a bulky framework than current SLAM lidar sensors. They gave the example of also using it perhaps in industrial vehicles, like detecting the position of forklift tines right on board the forklift itself.

Why it’s surprising: While utilizing a different technology, it reminds me of the old XBox Kinect where there’s suddenly a consumer-ready Time of Flight sensor on the market, it’s small, and easy to work with, and researchers are still using them today for their versatility. I think the potential applications of this little black box are only limited by the curiosity and innovations in their mind.

Gaussian Splats Graduate to Mainstream Tech

One of the most surprising trends at INTERGEO this year wasn’t a single flashy product or big announcement—it was the quiet, almost casual way that Gaussian splatting has found its way into mainstream geospatial technology. Just a year or two ago, this method of rendering 3D point clouds as continuous, photorealistic surfaces was considered experimental, the kind of thing you’d expect to see in research labs or cutting-edge visualization demos. Yet on the show floor, it seemed like everyone had some version of it built in.

Esri, Topcon, GreenValley International, Pix4D, GeoCue, PrevU3D, FJDynamics, Xgrids, and others all unveiled products, software updates, or plug-ins that incorporate Gaussian splatting in one form or another. This collective shift signals a major step forward in how 3D data can be displayed, interpreted, and shared — faster and more fluidly than ever before.

Why it’s surprising: Gaussian splatting is a relatively new and computationally demanding approach, emerging from computer graphics and AI research rather than traditional geospatial development. Its adoption across so many established players, so quickly, shows how eager the industry is to push past the limitations of traditional point cloud visualization. Instead of being a futuristic concept, Gaussian splatting is already here — and it’s quietly redefining what “realistic” 3D mapping looks like.

Takeaways

In the end, what stood out most at INTERGEO 2025 wasn’t just the individual technologies themselves, but the overall sense that the boundaries between once-separate domains are dissolving. The convergence of metrology and mapping, the miniaturization of high-precision sensors, and the mainstreaming of advanced visualization techniques like Gaussian splatting all point to a geospatial industry that’s evolving faster and more fluidly than ever. These innovations don’t just make data collection and visualization more powerful or more efficient, they make them more accessible, adaptable, and imaginative. If these examples are any indication, the next wave of geospatial breakthroughs won’t be about doing the same things faster, but about reimagining what’s possible entirely.