In 2021, the federal government enacted the Lead and Copper Rule Revisions, requiring every water system in the United States to create an inventory identifying the materials used in the pipes connecting water mains to indoor plumbing. The regulation emerged from a pressing public health concern: millions of lead service lines across the country continue to deliver drinking water, creating serious health risks, particularly when water sits in these pipes for extended periods. According to the EPA, some of the most concerning symptoms from drinking out of lead pipes are kidney damage, reproductive issues, increased blood pressure, hypertension, and memory loss. Some of the other common symptoms are headaches, fatigue, and muscle pain.

The deadline for water suppliers to submit their initial inventories to state agencies was October 2024, setting the stage for what advocates hoped would be a comprehensive understanding of the lead pipe problem across the nation.

Anticipating potential challenges in accessing this critical data, the New York League of Conservation Voters and their partners took action in 2023, passing the Lead Pipe Right to Know Act. This state law clarified what would happen to the data once state agencies received it from water suppliers, mandating that within four months of the October 2024 deadline, the information must be made publicly available and eventually mapped.

While the federal Lead and Copper Rule Revisions included transparency provisions requiring water suppliers to publish their inventories on individual websites, advocates wanted the data presented uniformly rather than scattered across thousands of different formats. In my own search for researching whether or not my drinking water in Maine was affected by lead piping, I was unable to find an easy answer. Further proving that data presentation and accessibility make all the difference.

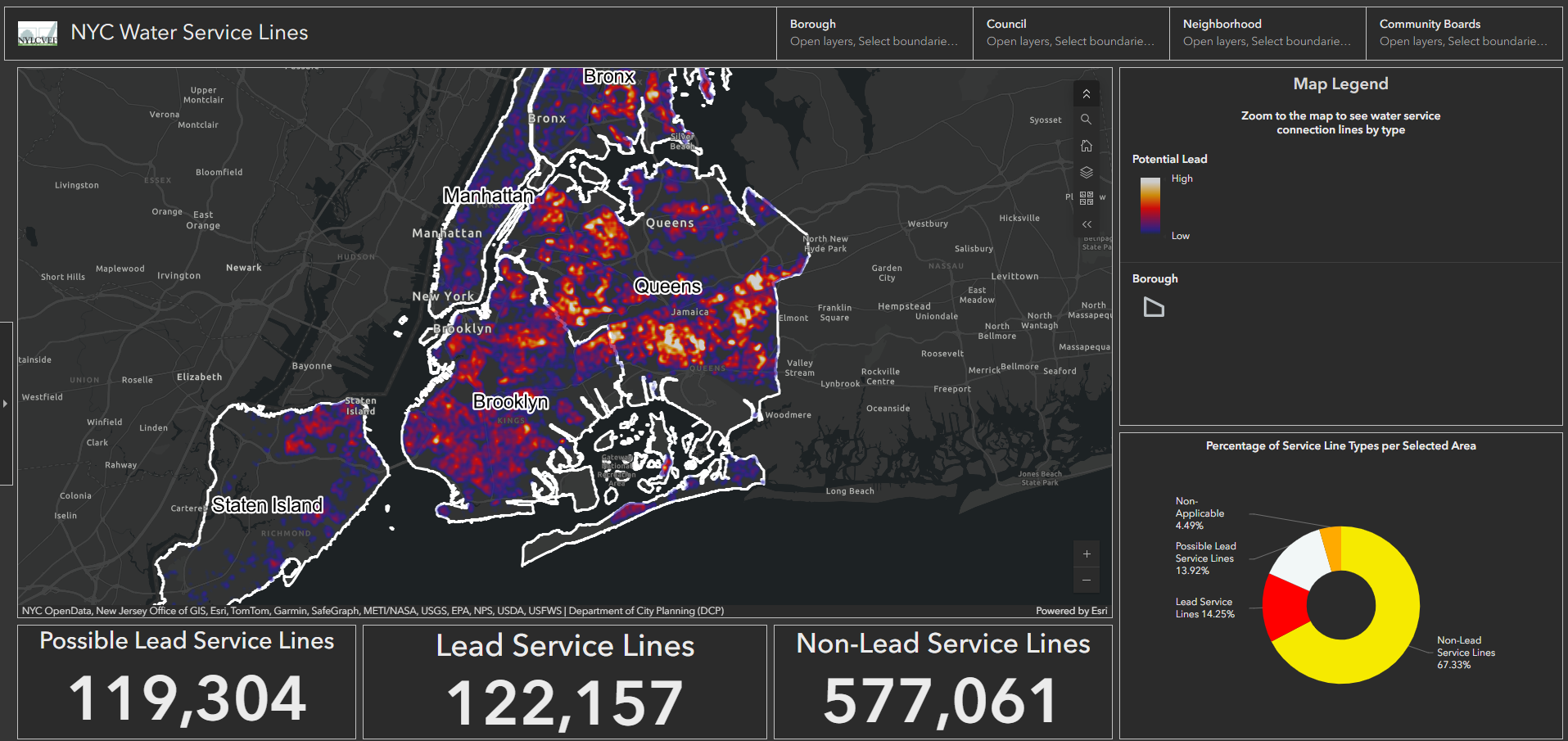

When the inventories were submitted in 2024 and data began emerging in spring 2025, a critical gap appeared: the state indicated it would take several years to visualize the information. Drawing on their experience creating a similar map for New York City in 2021, the conservation league decided to take on the statewide mapping project themselves.

Their interactive map provides multiple layers of insight. At the state level, a heat map shows concentration areas of potential lead pipes. The tracker reveals the scope of the challenge: approximately 3.7 million service lines statewide, with about 2.5 million confirmed as non-lead, 285,000 confirmed as lead, and nearly 1 million classified as "possible "lead" - meaning the material is unknown and hasn’t been documented.

Users can zoom from the macro state view down to individual properties, type in specific addresses, or filter by political boundaries like state senate districts. This multi-scale functionality serves everyone from homeowners checking their own properties to elected officials understanding the scope of the problem in their districts.

The response has been overwhelmingly positive, with significant media coverage and engagement from elected officials. The league has introduced state legislation addressing the issue, with the mapping tool helping guide those conversations.

"Every lawmaker when contemplating the plan knows what is going on in their district, as we're providing the visualization and the mapping for them," Josh Klainberg, Senior Vice President of the NY League of Conservation Voters Educator Fund, explains.

The map addresses a fundamental problem with the individualized notification approach. "There hasn't been any sort of public awareness of this being a community issue, as opposed to being a one-off issue for an individual," Klainberg notes. "And there hasn't been any sort of recognition of how big this problem is around the state and where it's located, which can then lead the conversations around how much money will be needed to fix it and where we get the financing from."

Despite the federal mandate, compliance hasn't been universal; New York still doesn't have 100% of the data from all water systems. The experience also highlighted that state government agencies can't always act as quickly as advocacy organizations in making data accessible to the public.

"Despite having all this information out there and available, it's still a struggle," Klainberg reflects. "You have to keep promoting this information so people can be aware of it."

As the November 2027 deadline approaches for water systems to begin their 10-year removal process, accurate inventories are crucial. "You want to measure twice and cut once," Klainberg says, emphasizing the importance of getting the data right before commencing removal operations.

This lead pipe mapping project exemplifies a broader trend: the democratization of Geographic Information System (GIS) technology for nonprofit organizations. Esri's Nonprofit Program, launched in 2010, now serves approximately 17,000 organizations representing nearly 100,000 users, not counting the countless people who interact with the maps and applications these nonprofits create. The program offers deeply discounted licensing and free training resources to 501(c)(3) public charities through a simple application process at esri.com/nonprofit.

Esri's roots in environmental work run deep; the company was founded in 1969 as the Environmental Systems Research Institute and began as a nonprofit itself. Today, the nonprofit program focuses on conservation and environment, humanitarian efforts, and community development, though it remains open to all types of nonprofit work.

Beyond lead pipe mapping, ESRI’s Nonprofit Program has helped provide GIS technology to innovative nonprofit work across diverse fields:

Conservation Science: The Jane Goodall Institute uses GIS to collect data on chimpanzee and ape habitats, with local community members serving as data stewards. Our Geo Week Keynote actually features Dr. Lilian Pintea of the Gooddall Institute, to discuss in depth the very ways GIS is being applied. "It's putting tools in the hands of people that live in the community and experience it every day so that they can become the data stewards for this place that is their home," Emily Swenson, Nonprofit Program Manager at ESRI, explains.

Electoral Integrity: The NAACP deployed GIS for real-time monitoring of polling sites, capturing patterns in challenges and intimidation so lawyers and legal aid could be deployed immediately to counter problems and protect democratic participation.

Wildlife Protection: The National Audubon Society's Hemispheric Bird Initiative uses GIS as a scientific method for understanding migratory bird paths, identifying challenges along those routes, and tracking how changing climate affects migration patterns.

A decade ago, GIS required specialized training and was often inaccessible to those without formal education in the field. The rollout of ArcGIS Online and other web-based tools has transformed the landscape.

"I think it's a bit of a golden age for nonprofits getting access and being able to use the technology to support the work that they're doing." Swenson emphasized.

She encourages organizations that think GIS is beyond their capabilities to reconsider: "What might have been impossible once is much more possible today."

The lead pipe mapping project demonstrates GIS's fundamental value in policy and advocacy work. While people may generally know that lead pipes pose challenges to communities, seeing data visualized on a map transforms understanding.

"Until you take that data out of a spreadsheet and visualize it in the form of a map, [it can be hard to understand]. But people know how to interpret a map. It's a pretty common visual language," Swenson explains.

"There's a huge benefit that comes from that simple step of visualization alone. Immediately, your brain starts to recognize patterns and see gaps and see trends by just looking at that data differently."

This visualization doesn't just raise awareness; it drives action. GIS helps determine where problems are worst, inform approaches to solutions, and, when combined with demographic data, reveal which communities have been historically disadvantaged and need prioritized attention.

The New York lead pipe map represents what Josh Klainberg describes as utility "up and down the chain from micro to macro," serving individual homeowners, community organizers, and policymakers alike. As water systems work to tighten their inventories before the 2027 deadline, tools like this will be essential for ensuring the work is done strategically and transparently.

To learn more about Esri's Nonprofit Program or to apply, visit esri.com/nonprofit. The New York lead pipe map can be found at the New York League of Conservation Voters website at https://nylcvef.org/lead-service-lines-in-new-york-state-interactive-map/