Climate change is an existential crisis creating new and varying risks everywhere across the globe, but in the United States perhaps no area is more at-risk for adverse effects than Hawaii. The Pacific archipelago is currently dealing with one of those effects, with recovery efforts just getting underway after recent devastating wildfires on the island of Maui. While that kind of event is felt immediately, other effects like sea level rise take on a more gradual process and require forward thinking and planning to mitigate the negative effects.

Issues like sea level rise, especially in places like Hawaii where you’re never too far from the coast, have huge effects on real estate and construction projects, where stakeholders need to think ahead to how their projects could be affected. That means not just keeping in mind how the coast looks today, but significantly down the road too, as most buildings are designed for long-term usage. On the island of Kaua’i, GIS technology is being used to ensure that long-term thinking is front-of-mind.

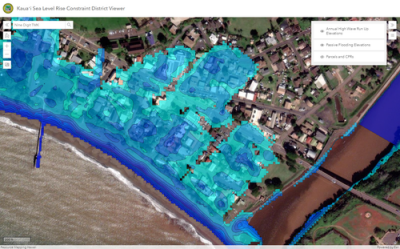

Using software from Esri, Kaua’i County has created a first-of-its-kind Sea Level Rise Constraint District, codified just under a year ago, designed to ensure any new construction is safe from sea level rise not only in the near future, but throughout the lifecycle of the building. To learn more about the district, Geo Week News recently spoke with Kaua’i administrative planning officer Alan Clinton to learn more about how the district came to be, how it works, and what other tools they could look towards to address impending climate change effects.

Developing the Sea Level Constraint District

Clinton tells Geo Week News that, even if this concrete idea may have been only recently made law, the idea of planning ahead for these types of scenarios goes back at least a decade. “Over probably the last decade or so,” he said, “through our long-range planning efforts, through our general planning processes, through our community planning processes, and a lot of our additional outreach events, people have been pounding at the door asking us for ways to preserve the special coastline areas that are very dynamic.”

This led to what could reasonably be considered the precursor to this Sea Level Constraint District with their Shoreline Setback Ordinance. This, which Clinton notes is similar to FEMA’s floodplain program, “uses historic datasets of shoreline erosion rates, and we created a formula that determined, if somebody wanted to propose a structure, how far away from the shoreline that structure would have to be based off the historic rate of erosion. This was our first effort to bake historic data into a regulatory framework for siting structures.”

Then in 2017, the state of Hawaii published a report regarding the area’s vulnerability to sea level rise and how areas can adapt to these risks. At its basic level, it looked at three major factors of sea level rise: Shoreline erosion, passive flooding, and bathtub elevation of water. The former had already been accounted for in their original ordinance, but Clinton and the rest of the team needed to determine: “How do we bake these new conditions about future projections of sea level rise hazards into our regulatory framework?”

Putting the Constraint District in effect

To do that, they looked to researchers at the University of Hawaii who had developed a model to project sea level rise well into the future. Clinton says that when Kaua’i permits structures, they expect them to have a lifetime of 70 to 100 years. With that in mind, using the data from the University of Hawaii, they created a visualization tool – available to everyone – showing projected sea level rise in 2100, in feet, around the entire island.

To comply with the new law, any new residential projects – or renovations which repair over 50 percent of the value of the structure – must be on lifts at least two feet above the projected 2100 sea level. Clinton notes that non-residential buildings must only be one foot above the future depth, and there are exemptions for structures like garages and other things with breakaway walls. Below is a video put together to explain how the district works.

With this kind of law, introducing a digital viewer in a way that has not really been done before, there’s a risk of frustrating some of the people like architects and contractors who have to reference this before any project. That hasn’t really been an issue in this case though, Clinton says, in part because they’ve been partnered with Esri and using their tools for years before this.

“Over the last five years in particular, we’ve been able to show more regularly how these technology solutions and tools can support not only planning, but functions such as emergency response and things of that sort.”

To ensure the smoothest transition possible, they worked with stakeholders. “This whole process that we vetted as this was going on, we made sure that we had this tested by land use attorneys, coastal engineers, and scientists to a point where the entirety of discussion at our council on this bill between two different meetings, a public hearing, a committee hearing, and the full council vote was less than two hours of discussion.”

The bill ultimately passed unanimously and was signed by the Kaua’i mayor. Clinton says that success is “due to the fact that the information was so readily available, and we made all these wraparound tools to make the policy a little bit more digestible.”

In addition to the visualization tool, Kaua’i also created a report generation tool for users. “One of the things that we oftentimes hear from people who are trying to submit information to us as a planning department is they want to be very accurate and very specific,” Clinton said. “This tool is designed so that if you print it, it can easily be associated with an application that someone submits to the planning department.”

What comes next?

This new tool and Sea Level Constraint District is not even a year old yet, but Clinton recognizes that the work does not stop now. He acknowledges, firstly, that the data from the University of Hawaii does skew more conservative, but notes that by codifying this digital tool rather than a physical map (which is typical for this type of law), they can make adjustments if needed. “If there is new data published from the University of Hawaii and some of our partners were able to take that data and insert it into the program, we don’t necessarily have to create a brand new policy,” Clinton noted. “We’re now letting the science inform the policy. When it is made available, we still have to go through our legislative process, but we will be updating the data rather than creating a new policy.”

Sea level rise is also just one of the concerns a place like Kaua’i has to keep in mind and plan for on a county level. Kaua’i is the oldest of the populated main Hawaiian islands, meaning that they have to deal more with things like runoff, which can be exacerbated in periods of heavy rain. Clinton says this is the area they could look towards next, though it’s easier said than done.

“The next model we’re looking at accommodating in a similar way are those associated with rain events, atmospheric models and how that rain interacts with our floodplain,” Clinton tells Geo Week News. “We’re eyes wide open looking at the international community of scientists who we hope will consolidate around some actionable figures that we’re comfortable working with.”

Developing this data is much more challenging than projecting sea level rise due to the inherent unpredictability of the events, but the scientific community has more data than ever before, a trend that only figures to continue for the foreseeable future. If and when that data does get to a reliable point and becomes widely accepted, Kaua’i will be ready.

“We’re looking forward to ongoing discussions in this space and trying to find a variety of new tools to better educate, communicate, and really seeing where this will take us as we navigate likely some pretty challenging conversations here in the wake of what we saw in Maui, and how we prepare for a variety of other hazards here into the 21st century.”

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)