Case Study by Matthew McMillion

The British Museum needed a faster, more flexible method than traditional photogrammetry to digitally capture more than 400 ancient Maya casts for the Google Maya Project, and so they chose Artec Eva, a high-resolution color 3D scanner. Their ambitious goal – for a 2-person team to be able to 3D scan hundreds of medium and large casts of Maya monuments in a crowded warehouse, and transform those scans into lifelike 3D models for cultural heritage, research, and educational uses.

When 16th century Spanish Bishop Diego de Landa ordered his men across the Yucatan to burn every Maya book and image they could find, calling them “lies of the devil,” in the hours that followed, centuries of Maya philosophy and cultural expression were lost forever. Only four Maya books survived his fiery wrath. But hundreds of miles away lay abandoned Maya cities teeming with pyramids, monuments, and other architecture engraved with Maya writing, also known as glyphs. Only in recent decades have a handful of scholars reached the point where they can understand 90% of what the Maya went to such great lengths to carve into stone, wood, bone, jade, and shell.

These glyphs tell stories of births, deaths, marriages, wars, conquests, and more. A cultural heritage beyond price for millions of modern Maya, and the entire world, yet every year more and more of these glyphs are becoming unreadable due to the ravages of acid rain, sweeping in from hundreds and even thousands of miles away. In the words of Dr. Pablo Sanchez, a biologist from the Centre of Atmospheric Studies at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, “We could lose all of the inscriptions and writing on the stelae and columns within 100 years.” Cultural heritage specialists have been searching for solutions, so far without success.

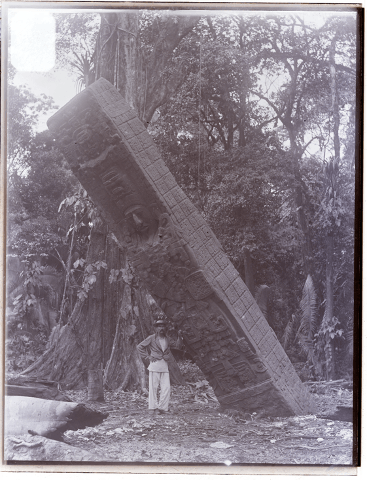

Quirigua Stela E, circa 1880s

In the meantime, the British Museum in cooperation with Google Arts & Culture embarked upon an exciting project to preserve and even bring back some of this cultural heritage to the Maya and the rest of the world. To do this, they used a synergy of the latest 3D scanning technology combined with the work of 19th century diplomat-explorer Alfred Maudslay, who together with a team of enthusiastic specialists and four tons of plaster, ventured across the Atlantic to the land of the Maya. There, using the finest technology of his era, dry-plate photography, plaster and papier-mâché molds, along with his handy notebook, he set out to preserve for his and future generations an astounding record of Maya art and architecture.

Once back in England, everything was brought to the South Kensington Museum (today the Victoria & Albert Museum), where the molds were transformed into highly-precise casts, effectively freezing in time dozens of the most important Maya monuments, all their glyphs and iconography, just as they were found in the 1880s, before acid rain began to sink its teeth into them.

To highlight the complexity of the work that Maudslay and his team undertook, archaeologist and British Museum curator Claudia Zehrt explained, “A regular monument required anywhere from 600-1000 individual segments of plaster that later had to be pieced together to create the final molds that were shipped back to England. These were essentially ‘negatives’ of the monuments, capturing all their characteristics in plaster or papier-mâché. Then back in England, the ‘positive’ casts we have today were created from these same molds. These casts are highly-accurate replicas of the original monuments themselves, which makes them perfect for historical purposes.”

The very foundation of the Google Maya Project demanded creating incredibly lifelike, historically-precise 3D models of the casts. With a background in photogrammetry, an often-popular method of digital capture among archaeologists, Zehrt quickly began to see the difficulties of using the same for the collection of Maudslay casts. In her words, “Basically there are hundreds of large, very heavy plaster casts sitting on low racks, 2 inches above the floor. The casts range in size from 3 x 3.5 feet to 8 x 9 feet or more. It takes several people to move them, and they’re also quite fragile. Many of them are only 11 to 15 inches apart from each other. So that ruled out photogrammetry, because we didn’t have enough room to shoot from all the angles needed to make that work. Even if it had been feasible, considering the lengthy setup and post-processing that photogrammetry entails, it would’ve taken us more than twice as long as it did with our Artec Eva.”

British Museum Curator Claudia Zehrt 3D scanning casts of Quirigua Zoomorph P with Artec Eva

Made available to them via Google, the Artec Eva, a handheld professional 3D scanner designed to quickly capture medium-sized objects in high-resolution color 3D, was new to Zehrt. Even so, she quickly got up to speed with it. At first the Museum didn’t believe that the Eva would be able to capture the casts under such cramped conditions, but Zehrt wasn’t one to give up easily. “Even considering the most awkward positions that I put myself into, because of the tight spaces, Eva scanned the casts just fine. Whether that meant sometimes mounting Eva on a monopod and extending it upwards, or contorting myself when there wasn’t room enough to kneel down, Eva captured all the surfaces of the casts perfectly, including the deep undercuts of the casts, which would be challenging even under ideal conditions.”

She explained in detail about her scanning process, “On average it took about 10 minutes to scan each cast. Small casts were faster, while some of the big ones required 20 minutes or more. It also depended on how deep and narrow their carvings are, since this makes it harder for the scanner to pick up those difficult-to-access surfaces. And if there had been more space between the casts, it would’ve been easier and faster. The 11-15 inches that I had certainly slowed things down. If the casts would’ve been free standing, with no obstructions, I could’ve easily scanned them in half the time.”

British Museum Curator Claudia Zehrt 3D scanning Maya casts with Artec Eva

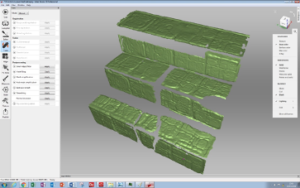

Zehrt went on to describe her work post-processing the scans in Artec Studio, “My usual workflow started with aligning the scans of the cast using Global Registration, then applying Sharp Fusion, and in the odd event that there was a hole in the scan, using Fix Hole to seal it up. I reduced the triangle count down so the final 3D model for export with texture was less than 100MB, while making sure that it still looked fine. Then I exported the model as an OBJ file. To look at it time-wise, after just 5-10 minutes of input from my side, Artec Studio took care of the rest of the process, and I was free to go off and do other work. Artec Studio does most of the heavy lifting for you.”

The first stage leading into the Google Maya Project involved creating a 3D model of Quirigua Stela E (consisting of 31 separate casts, in total, standing 22 feet tall), one so precise and lifelike that it could be used for educational purposes as well as detailed iconographic analyses by Maya specialists. This stage was vital to demonstrate that 3D scanning with Eva, along with post-processing in Artec Studio, would be a fast and effective solution for Zehrt’s two-person team to digitize the entire project’s collection of 400+ casts in high-resolution color 3D.

As can be seen in the following video, where Stela E is featured as a VR object being studied by Maya epigrapher Professor Christophe Helmke, the results speak for themselves:

Zehrt shared some details about Stela E: “We now know that this monument from 771 AD describes the Maya king of Quirigua, Kʼakʼ Tiliw Chan Yopaat, also known as Kawak Sky, capturing and decapitating another Maya king, Waxaklajun Ub’aah K’awiil, also known as Eighteen Rabbit, the ruler of Copan, a larger Maya city, who had actually put Kawak Sky on the throne years before. There’s a glyph that features a stone axe for beheading, and on the front of the stela you can see the victorious king (Kawak Sky) wearing all his ceremonial attire, headdress, jewelry, and so on. This was a huge event for him and his people, since it meant their liberation from being under the power of Copan. Not to mention that this is an extremely interesting monument. The original weighs 65 tons and towers more than two stories above the earth.”

- The Hieroglyphic Stairway of Palenque, circa 1891

- Scans of the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Palenque in Artec Studio software

- Mock-up of the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Palenque replica, created by Pangolin Editions

A subsequent stage of the project focused on creating an exact CNC-milled replica of the Hieroglyphic Stairway of Palenque for display alongside the original stairway. Dating back to the 7th century CE, the condition of the stairway has deteriorated considerably since 1891, when Maudslay captured it in plaster. Historical details and translations of the stairway can be found here.

The stairway casts presented some challenges for 3D scanning and digital reconstruction, as Zehrt explained, “The stairway consists of 12 casts, all of which were 3D scanned with Eva, which went smoothly and quickly. But because one of the casts was broken and some of the detail was missing, we needed to refer back to Maudslay’s original drawings and photographs of that step in order to recreate it digitally in its entirety. And we succeeded.”

At that point, Zehrt turned to Artec Ambassador Central Scanning for help with creating the final 3D model of the stairway, since it required seamless 3D bridging at the junctions between the steps. Experts in 3D scanning and post-processing, over the course of a day, the specialists at Central Scanning digitally assembled the scans in Artec Studio 14, turning them into a unified 3D model ready for CNC milling in six separate panels, for ease of transportation.

The 3D model of the stairway was then sent to Pangolin Editions, where it was CNC-milled out of Ancaster limestone, from Lincolnshire, England, a Middle Jurassic oolitic limestone quite similar to the limestone the Maya used for the original stairway. Pangolin Editions is a Gloucester, England-based foundry specializing in sculptures. The slightly different color of the replica is intentional, as Zehrt explained, “The conservators of the site want people to know that it’s a replica and not the original. People will be able to walk up close and touch it, to run their fingers along the glyphs and experience this amazing cultural treasure firsthand.”

Following CNC milling, the stairway was flown to Palenque for permanent display alongside the original. Future possibilities for the 3D models of the casts include research projects by Maya specialists and academics worldwide as well as educational applications such as “virtual field trips” for classrooms and museum visitors, for example, this event at Preston Park Primary, a multicultural school in Wembley Park, London.

And in the words of Claudia Zehrt, “We are just at the beginning of seeing what we can do with 3D scanners and the remarkable models they can create of priceless cultural heritage around the world. Beyond the research benefits of 3D scanning, as well as the incredible possibilities we’re seeing with turning these objects into VR exhibits, there’s something equally if not more important. That’s using this technology to return these treasures back to the people, to the cultures that created them. Today using a handheld 3D scanner like Artec Eva, I can digitally capture in minutes almost anything on display in a museum, or even onsite at an archaeological excavation. After only a bit more time using Artec Studio to post-process the scans into a 3D model, I can send it to a 3D printer, or in the case of the Palenque Hieroglyphic Stairway, have it milled out of limestone or various other natural materials, wood, stone, etc. This means that museums around the world can have the power to create incredibly lifelike replicas of these artifacts, yet ones that people can actually touch and hold. We’ve never had this ability before.”

Through Google Arts & Culture, the British Museum has made available its complete Maudslay archive of scanned photographs, diaries, drawings, and 3D-scanned casts are available on the Maya Project website.