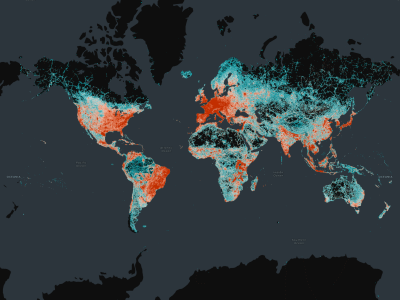

As accurate and consistent location data has become even more of a must-have for businesses in recent years, with the advent of smartphones, among other technologies, many companies have sought to create their own internal maps over the last couple of decades. However, most have found that this process is far more complex than they would have originally believed, leading to more of an emphasis on an open data ecosystem for geospatial. This benefits not only these private companies but also public organizations and citizens around the world, who have greater access to what can be life-saving data in some scenarios.

This growing enthusiasm around open data led to the founding of Overture Maps Foundation in late 2022, and the organization has since released its first open dataset and continues to grow. Amy Rose, Overture’s CTO, participated in a panel at this year’s Geo Week conference talking about the growth around open data in the geospatial industry. Recently, Geo Week News followed up on that conversation, talking with Rose about industry attitudes around open data, how Overture works with governments around the world, the impact this data has on public safety in emergency response scenarios, and more.

Below you can find the full conversation, which has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Geo Week News: Tell me about your role with Overture Maps Foundation.

Amy Rose: I'm the CTO at Overture, so really what I do is all about the engineering and operations side of things. That's anything from working with all of our different task forces and working groups on the technical strategy to deep diving some of our bigger efforts, like our Global Entity Referencing System (GERS), and getting into the technical weeds of the implementation.

What was the impetus for starting Overture, and what's the broad mission for the organization?

The founding companies - Microsoft, AWS, TomTom, and Meta - realized, Hey, we’re all doing the same thing, building this map data, and in some cases the exact same thing. The reality is most of that was pre-competitive. It's not work that was really a business differentiator, but they all needed it for their business. They wanted to collaborate for cost savings and efficiency, but also the idea of making it an open project so that the benefits could go beyond just building a base map. What I mean by that is the interoperability piece is a big part of what we're doing with Overture. It's not just about building a reference map, but it's about being able to link other data to that reference map very easily.

When we think about interoperability, we're used to thinking about standards, and certainly schemas, but what we're really going for is this idea of reducing what we call the conflation tax. The challenge that everybody deals with can be more difficult in geospatial, because you're also dealing with geometry. That conflation when you're trying to put a variety of datasets together can become very expensive, and you see it going on not just in industry, but in academia and public sector as well. We’ve moved into this space where it's not just about how can I make a map or do some analysis for a small area, or how can I generalize a view of a larger area, but I want very detailed information about any area at any time. Now, we're getting into this tradeoff between urgency and fidelity. To be able to have both you need that interoperability to be easy.

Recognizing that it's still relatively early days for you all [Overture was officially announced in December 2022], which individual industries within the private sector have been more enthusiastic to this concept of open geospatial data, or have maybe been the early adopters?

I wouldn't necessarily say specific industries. What I would say is use cases. For example display. That's something a lot of organizations need - a map for display - and want to have something that's high-quality, enterprise-grade, and easy to keep up to date. That's a big one.

The other big one is local search, which is related to everything that you do on your mobile device, everything with how we connect with the world today. That touches many of our members, but also the broader industry: How do I interact with places? How do I get from A to B? The kinds of geographic, spatial and location questions that you ask of your digital device every day. So that's a big one. Routing and navigation are also ways that members and others are using Overture.

Something that doesn't bubble up as a specific use case, but is layered across all of them is using geospatial data for business intelligence and treating geospatial data as another column or set of columns in your BI tools where you can do any kind of analysis. It doesn't have to be specifically spatial, but you can factor in this location information to support additional business analytics.

Do you have those kinds of conversations with people in companies that may be able to utilize that, but who maybe aren't thinking about it? When you do, is it a light bulb moment for them, or is it a lot of follow up questions and wanting to learn more?

I think it's a little bit of both, depending on who you're talking to. There have been more light bulb moments than I would have imagined. When people talk about geospatial data, you're always thinking about something visual, something map related. The reality is, that's been a bit of a blocker in terms of how people use spatial data, because they’re not thinking about using the standard tools that they work with every day, for example doing table queries. They're thinking about, Oh, do I need this special tool to use spatial data? And the answer is: No, not anymore.

I think the more we talk about it, the more people realize, I can use all the same tools that I'm used to. This is especially true in the cloud environment with all the tools that are available there to do data analysis. Now you have more and more of those things that are starting to work natively with spatial data, and it just becomes another data type. I think people that are working in cloud environments understand: I work with these kinds of things all the time. I query parquet files all the time, or, My business intelligence is built on tables with rows and columns just like this is. I think they understand that. Other folks, I think, are catching on, but it's varied.

And then on the public side, a lot of your information is being pulled from public entities, and that's just open for everybody, but I'm wondering what kind of relationships you have in the U.S., but also internationally. Are they also pulling from you? Is there that push and pull relationship with the public entities, whether it's national or local governments?

There's some of that, yes. We'd like to see more. The conversations that we've had at all levels is: What is the best way to do that? We’d like to add publicly available data to Overture in two ways: as part of our reference map, and as richer information associated with the reference map via GERS. Overture data is already being used in platforms that people are using every day like TomTom’s Orbis Maps, Esri’s Living Atlas, Bing Maps, Facebook, and Instagram. So, if we add public data to improve Overture’s Transportation layer for example, that data will make its way to those and other platforms that use Overture.

But there’s also the information beyond the reference map that’s useful. If I want to see what’s on my route from Chicago to Charleston, is there construction or road closures? The easiest way to get that now might not be very easy. Most state DOT’s post their road closures on their website and even with interactive maps, but I’m not going to go to each website to look at that and try to relate that to the map I’m using – Where's mile marker 135?

What we're saying is we want to make sure that we’re including that public road network data, which will already have that explicit link to that kind of road closure data, or where the potholes are, or whatever it is, that linearly referenced information, so that it’s easy for anyone using Overture to consume. We're thinking about it as a way to get public data in a more visible space for use, getting it out to more people. Somebody I was talking to recently in the public sector referred to that concept as using Overture as a shop window for their data. It will get more exposure and be used by more people than if it’s only posted to their website.

When you think about the capacity that some organizations have, maybe at a state level they have a lot more capacity, depending on the state. On a local level, if they have this kind of information, they might not even have the capacity to post it on their website. How can we make sure that that kind of information, which is particularly useful, gets out to more people? That's the beauty of having an open reference layer.

What's holding that back from happening? Is it just a matter of governments having other things on their plate, so it's just not the top of their priority list?

I think it's a combination of things. One can go back to capacity. Yes, it might not be a priority. From our perspective, the ideal situation would be to work at the highest level. Looking at U.S. data, what’s the highest point of collection that can come into Overture? Does it make sense to do something at the federal level? Or, depending on the update cycle, would we actually be better off doing things at the state or county level? The more things that you add in at those lower levels, now it becomes a tougher thing to maintain.

But I think the other part of it goes back to interoperability. We've got a lot to do and we're still in very early stages, but the interoperability piece is the piece that's going to be most important. That's going to provide that connective tissue. So even if it's something that's posted on somebody's website, if we can get that data propagating through the GERS ecosystem, then it really does become much easier. Even if I have to go grab this data from a state DOT website and join into my own data, it still makes it much faster to do that. So it’s certainly capacity, but it's also building out that interoperability piece to grease the skids for that data exchange to happen more easily.

As somebody who doesn't work directly in this field, it sounds daunting to try and implement GERS as this kind of standard. You've spoken before about this in relation to the National Spatial Data Infrastructure. Is that about having conversations with relevant parties in the federal government and trying to start at the top and hoping it funnels down?

The federal level is the right place to start, but the National States Geographic Information Council (NSGIC) is an important piece of this as well. There's some things that happen at the federal levels that might not be the right collection point. There might be better data, fresher data, at lower levels, and just because of the cadence of the required updates, that might be the better spot. It's having a lot of conversations with them about: What is the right path here? Is it better for this to be something where Overture gives you an easy push option? Is it something where we find the right pull option?

But we want to make it work for everybody. We want to make sure that we're getting the right data from the right places, and that it provides value back to those users. I guess you could call it daunting, but really it is - and it has been my entire career - the biggest challenge in geospatial. Somebody has to solve it, because we keep kind of running up against the same thing no matter what we're talking about, whether it's the NSDI, whether we're talking about the commercial sector where they're trying to bring together a bunch of data from different vendors, whether we're talking about emergency response, we have to solve that interoperability problem.

I guess I don't look at it as daunting. It's a big challenge, but I think it's fun, and it's something that, when we're successful, will be a huge step forward for this industry.

Obviously, we've been talking about the U.S., but Overture is an international organization. What is the complication of then having to, for example, go over to the EU and do those same processes and then make everything match. Is there added complication there?

I wouldn't say added complication. We always have to be aware of everything from licensing to privacy. One of the things that we were very careful about in the beginning was making sure that we had a way to address any data takedown requests. If anybody had a specific reason why something should be taken out of our dataset and we could verify that it was a valid request, we would do that and follow guidelines that have already been set, for example GDPR. We've already put a process in place to make sure that when we do get those requests, that we handle them in a certain way, that we make sure that we're following those guidelines.

I think the complexity is really more about awareness and making sure that we're doing the right things, particularly around licensing. We're very focused on making sure that the licensing is right, making sure that just because the source that we're getting the data from says it's a certain license, if they weren't the original source, that we're not passing through something that shouldn't be passed through. Those are the complications. The geographic complications are more about how different organizations work, and I think that's true whether you're international or domestic.

You mentioned emergency response earlier, and we talked a little bit about this at the panel at Geo Week. I'm wondering if you could talk a little bit about how this open data ecosystem works to help with this emergency response work.

I think the big thing, thinking about natural disasters, is that there's no boundaries. They're going to happen where they're going to happen, and they're going to cross county, state, national borders. Thinking about the way that we have traditionally dealt with geospatial data, usually they're in those geographic silos. Here's U.S. data, or here's the state of Tennessee data, or here's Knox County data. If we've just had an outbreak of tornadoes and it's crossed 20 counties in three states, how do I quickly pull all that together?

Natural disasters, I think, are the biggest reason why interoperability is critical, because you don't usually have a lot of time. Even with things where you do have warning, like hurricanes, you don't have that much warning, and you really don't know until post landfall what the geographic extent of the event is you're dealing with. It's about being able to pull things together very quickly, regardless of the format, regardless of where it sits, but it's also about being able to have a complete base map.

Somebody could just start with Overture data. Hey, I need a quick map of the area that shows the roads and the boundaries and places and buildings. That's our starting point. And then the GERS aspect of Overture provides that interoperability to where now I can link other kinds of richer data, whether it's additional information for features in that area, or overlay my own data on top of that to add detail to the map. Every time I think about what Overture is doing, I think if we can fit that emergency response use case, then we’ve checked a lot of boxes.

Last question: What's next for Overture? What are the sights set on moving forward?

Right now the big thing is GERS. We've had what we would call GERS Version Zero so far; we've had the IDs. But really bringing it all together as a system with the reference map, persistent IDs, and traceability of those IDs in their life cycle, all of that is coming together now. In March we published GERS bridge files for the first time. We're targeting the June release to put out a variety of things so that now users can really use GERS as a system.

If we're talking about what's next after that, the other big one is data quality. If we're putting out this system where we want to support interoperability, then that reference map should be of high enough quality that people can rely on it. We’re going to have a lot of different data quality efforts that will be more transparent to users in the second half of this year. We want to be able to say: Here's our pipeline for how we validate data. Here are the types of validation that we're running. Here are the issues we're detecting. When we detect issues, we want to be able to report those back to the data owners or stewards to help improve data quality at the source. I think that the two big things are certainly the maturity of the GERS system, but then the data quality that underlies it.