In today’s modern society, access to consistent, high-speed internet is no longer a luxury; it’s a necessity. Modern education and professional responsibilities often rely on this access to broadband services, but for many around the country, this access is still limited by outside factors. Whether it’s affordability or simply a lack of access, millions of Americans are still unable to get this consistent internet access. These issues are particularly prevalent in rural areas, where the infrastructure required to provide this consistent access is often lacking or simply nonexistent.

As part of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, also known as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which was signed into law in late 2021, the federal government earmarked a $42.45 billion grant program aimed at connecting every American to high-speed internet. As a result, states and local organizations around the U.S. are funding projects to ensure access to high-quality broadband services in rural areas around the nation.

Maine is among the states using this grant funding to serve the rural communities spread across the state. By some measures, Maine is considered the most rural state in the U.S., with one measure estimating that over 60 percent of the state’s population lives in rural areas. Geo Week News recently spoke with representatives from the Maine Connectivity Authority (MCA), as well as the Center for Geospatial Solutions (CGS), to learn about these efforts and the critical role played by GIS in delivering this access.

As part of the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program, which provides funding from the aforementioned Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, Maine was provided with a $272 million grant to bring this digital equity to their citizens. As Meghan Grabill and Jessica Perez, the director of research and data and digital equity manager, respectively, for MCA, explained to Geo Week News, two initiatives are being put into place to increase broadband access, both of which leverage the powers of GIS.

One is directly related to the BEAD program, which provides a system for internet service providers throughout the state to bid on connecting certain areas to broadband access. This process leaned heavily on GIS tools and geospatial information, with Grabill leading the way within the agency to complete this work. As she explained, one of the big turning points in this work came from a data change in 2022.

“Before, the data was shown at the census block level,” Grabill said. “If you had a house in [that block] that was serviced, the whole census block was considered served. In 2022, data came out that was every single household and business - every structure that could consume broadband.”

With this new granular data available, the agency could derive a more accurate picture of broadband access across these rural areas. That data was then combined with spatial data showing the existing broadband infrastructure across the state, which came from both publicly available and private sources. This is where the CGS came in, as associate director of data visualization Justin Madron explained.

“We worked with Meghan and her team to come up with the data workflow that programmatically grabs that [infrastructure] data and gets it in the format that they need, so it can be easily accessed and used.”

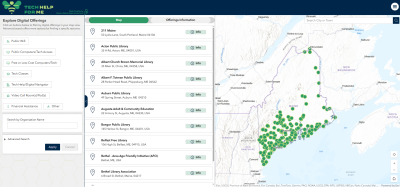

Along with this infrastructure and access mapping program that forms the backbone of providing direct broadband access to households throughout the state, Perez led a separate effort from MCA called Tech Help for ME. Also leaning heavily on GIS tools, this platform allows residents throughout the state to easily and intuitively find places where they can access technology based on their location. The tool includes the ability to search for offerings, including public WiFi, public computers, tech classes, financial assistance, and more. While the BEAD program’s project leaned heavily on geospatial expertise, Tech Help for ME was assisted in many ways by putting less focus on robust geospatial offerings to make it user-friendly.

“When you think of traditional GIS tools, they are not usually created for people who aren't computer savvy or don't have a good internet connection,” Perez said. “What I think is really special about the work that we did was how we used these tools and adapted them for a different audience, and made sure that they have access to data visualizations and geospatial tools, but in a way that is appropriate for someone who didn't use this in a college classroom.”

For both of these projects, collaboration was among the key factors that made everything work smoothly. That collaboration came internally within the team, externally with teams like Madron’s and Esri, and with the community as a whole. Sticking with the Tech Help for ME tool, Perez noted that she and her team worked extensively with the public to ensure that those who will actually be using this tool can do so intuitively.

At Esri, their director for telecom industry solutions, Randall Rene, explained that these projects in Maine shared similarities with similar initiatives around the country.

“I think what Maine did is both familiar and different. On the familiar side, most states and providers we work with are trying to do the same thing: use GIS to plan broadband expansion smarter. It’s about seeing where the big gaps and needs are, lining that up with existing infrastructure, and making sure investment dollars go where they’ll have the most impact. Maine used GIS the same way, mapping BEAD-eligible locations and giving providers tools to bid with confidence.”

There were some key differences in what Maine has been able to do compared to other states around the nation, though.

“This one, I think, is very different from a lot of other projects,” Madron explained when asked what he could take away from this for future projects with other clients. “It’s how comprehensive I think this is. It’s not only thinking about setting up the infrastructure, the system that can support these types of projects, but also thinking about how all of this stuff interplays together and can be used across all of them.”

Rene agreed that this work went above and beyond what he’s seen from other states, specifically pointing to the Tech Help for ME tool.

“What stood out to me was the second piece. A lot of projects like this stop at building infrastructure, where Maine also leaned into tackling digital literacy. I love how they rolled out the Tech Help for ME site and app so residents could easily and quickly find WiFi spots, computer classes, and other resources in their own communities. It wasn’t just about getting fiber in the ground; it was about making sure people knew how to use it once it was there. That’s not something we see everywhere, but it’s a beautiful and powerful model.”

Grabill attributes some of their success to the unique model by which they operate. While most state broadband offices operate within other agencies, such as the Department of Transportation, MCA is a “quasi-government agency,” which allows it to be a little more independent and not tied to systems being used by a parent agency. When asked what advice she would give to other agencies, beyond becoming this kind of quasi-government agency, she recommended collaboration.

“The advice I would give is to work with partners like CGS, and regional and tribal members, as well as the entire ecosystem of broadband partners. It’s starting there, and having the expert advice from the crowd instead of being an individual expert. This has driven us to the point we are, because it’s more comprehensive this way, and the users are actually interacting with our tools.”