The U.S. General Services Administration is spearheading the National 3D-4D-BIM Program, an initiative to drive use of 3D, 4D and building information modeling (BIM) technologies to improve management and delivery of GSA capital projects. Last week we reported how the Office of the Chief Architect (OCA) in GSA’s Public Buildings Service (PBS) won funding to investigate the application of 3D laser scanning to 3D-4D-BIM, and how service providers can apply to participate. Today’s article describes GSA’s business case for laser scanning, presents lessons from an initial pilot, and details open issues that GSA seeks to address in its OCA pilot projects going forward. These articles are based on a presentation by Dr. Calvin Kam, National 3D-4D-BIM Program Manager, Office of the Chief Architect, Public Buildings Service, U.S. General Services Administration, to attendees at SPAR 2006, March 27-28, Sugar Land, TX.

GSA business case for 3D laser scanning

“GSA is not unlike any private real estate company,” Kam explains. “GSA PBS manages and delivers space for other federal agencies. Its revenue relies on accurate space counts and billing invoices to its tenant agencies. How we manage spatial information and building assets definitely affects our business. Being able to capture existing conditions accurately affects us all the way from historic preservation, design and construction through facilities management.”

GSA classifies the buildings it manages into three categories: historic buildings, mid-twentieth-century modern buildings, and new design/construction. “We have over 200 buildings in the National Register of Historic Places,” Kam reports. Even so, the majority of buildings managed by the GSA are either mid-twentieth-century modern structures, or contemporary designs. For each, 3D laser scanning offers a distinct value.

“The business case we developed,” Kam explains, varies by building type. “The challenge for historic buildings is that we may not even have as-built drawings. If we need to go into the space, how can we make sure we are not invasive and don’t hurt any of the existing ornamentation?” The value of 3D laser scanning for this is evident.

With mid-century buildings, “in many cases these are going to go onto the National Register of Historic Places once they become 50 years old. So it is imperative for us to take good care of them.” Again, 3D laser scanning is proving an ideal documentation tool.

With contemporary designs, “we see that 3D laser scanning can add value here. Even though these great designs were developed in 3D, we still don’t have a way to capture those as-designed and as-built conditions. When we come back to the completed building to measure the space, people still rely on 2D polylines to come up with the rentable square footage.” But the complex, irregular geometries common in these structures make it hard to get accurate measurements using traditional methods. “This is where we think we can use laser scanning to capture the existing volumes.”

Continued…

Pilot project – 26 Federal Plaza, New York City

“As with our other 3D-4D-BIM technologies, we started by doing a laser scanning pilot case,” Kam reports. GSA’s first laser scanning pilot was 26 Federal Plaza, a mid-century building near Broadway in New York City built about 30 years ago. The laser scanning project, executed in 2004, was carried out in collaboration with GSA Region 2, Optira (Omaha, NE), Leica HDS and the project team.

“The field conditions were an existing plaza with hundreds of visitors every day.” Because the building lacked an entryway facility suitable for security control, “we decided we wanted to create an entry pavilion both for security and to create a good impression for visitors.” Laser scanning was ideal for several reasons: The new entryway was to be situated within the existing structure. There was existing sculpture in the vicinity that had to be maintained. There were underground utilities that needed to remain in place.

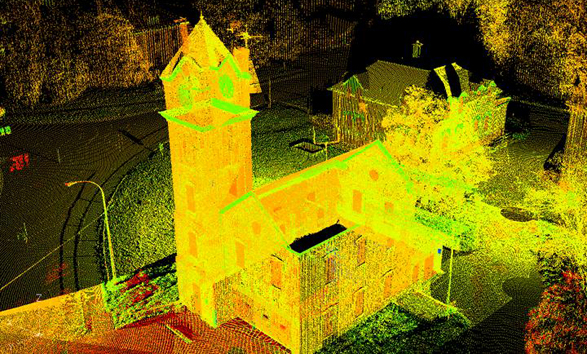

“We spent two and a half days performing laser scanning,” Kam reports. “Then the conversion to a 3D model took another 40 man-hours.” The next step was to “put 3D laser scanning into the context of the 3D-4D-BIM program.” A 3D laser-scan-derived model was delivered by Optira. “With that as the base for the design,” Kam says, “I built another 3D model of the designer’s proposal,” and then superimposed the two models.

What did this reveal? For one thing, a wall shown in a 30-year-old design drawing was shown by laser scanning to be five feet away from where the drawing showed it. With the project “at 35% of construction documentation, we got that piece of information” – a real time- and money-saver for the project. “The ability to be proactive – to find out these problems early on – means a lot to GSA.”

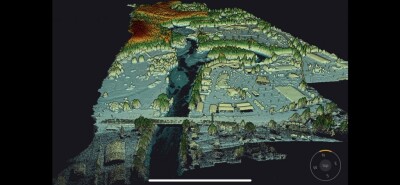

OCA took the lessons learned on this project and is using them to advise another GSA project that is ongoing at present – the St. Elizabeth campus, a historically significant site in southeastern Washington, DC. Here, the GSA National Capital Region Portfolio Management Division wanted to capture the structure’s existing conditions “so that we will always have a comprehensive documentation of the site and its buildings.” This project, which involves scanning about 60 buildings on the site, is about 80% complete. Some of the scan data has been used to create 2D documents to provide the master planning team with plans, elevations and sections of existing structures. At same time, data is being used to create 3D Building Information Models of the existing facilities.

Why 3D-4D-BIM? With such a model, “we don’t have to reference so many different sheets or drawings,” Kam summarizes. “We can have one central source of information from which we can take plans, sections and elevations.” This approach “also helps us with master planning efforts. The project team can take all these buildings, stitch them together, then tie in all sorts of other information – topographic information, tree canopies, Google Earth data, ESRI data” and more.

Open issues

Some open issues that Kam hopes the pilots will help answer:

- Scope of work, evaluation criteria, budget, scheduling – “How do we define these before we make the go/no-go decision on laser scanning?”

- How to document hidden conditions? “We know that laser scanning requires a clear line of sight. But every time I go out and speak, project managers ask me, ‘Can we get at unseen conditions – things buried underground or hidden inside walls?’ Can we bring GPR and similar technologies available into these pilots?”

- Is it necessary to convert laser scan data into a 3D model/building information model? “In some cases we are finding that, if we keep the point cloud intact and superimpose a 3D model on top of it, without converting the cloud to a 3D model, that may sustain the project.”

- How to properly integrate building information and geospatial data with 3D geometries? “A lot of BIM tools let you build a clean model with straight walls, but when you have distorted walls or sagging conditions, how can we convert those geometries into 3D solids with building intelligence?”