Data, and its value, has been at the forefront of media discussion for the past couple years. It has been often described as the new oil. So, often, in fact, that there are now many people stridently arguing that it is not the new oil.

Regardless, it is clearly true that we have mountains of data right in front of us and our goal is to extract that value and derive actionable insights into how we can deliver products or services better or with less cost.

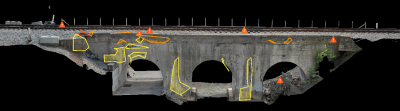

But “data” is a broad term and in the built environment this definition can be expanded even further. We deal not only in the digital but also in the physical. Until recently, this cyber-physical data was not easily accessible or understood, but with the unfortunate circumstances in Paris at Notre Dame, many have seen that the recreation of the landmark may be possible with the use of reality capture techniques, piquing interest in the technology globally.

But if data is the new oil, it’s important to know who owns it. Take the example of Notre Dame, which was captured by Vanderbilt University Professor Andrew Tallon as part of a project roughly a decade ago. Is the data Notre Dame’s? Vanderbilt’s? Tallon’s estate’s?

But if data is the new oil, it’s important to know who owns it. Take the example of Notre Dame, which was captured by Vanderbilt University Professor Andrew Tallon as part of a project roughly a decade ago. Is the data Notre Dame’s? Vanderbilt’s? Tallon’s estate’s?

In the oil business, this can be a very lengthy discussion and include many nuances, specifically regarding mineral rights vs property rights and a cornucopia of other terms. Usually, land owners are not looking to keep the raw oil found on their property. There are heavy processes for extracting such oil and then additional processes to manipulate and refine the oil for use elsewhere. Land owners would most likely be interested in payments for access to the oil, rather than keeping it for themselves to avoid ever having to visit the fuel station.

Certainly, data is like oil in that it is not immediately consumable without processing and requires specialized tools and professionalism to refine it for consumption. Where the “data is the new oil” analogy falls short in the built environment, however, is with the value proposition of reality capture data. While landowners rarely ask for the refined oil back as part of their deal, many owners are beginning to see the value of extracted 3D data for the operation of their facilities — not just the construction stage. And that greatly changes the value dynamic.

The traditional goal of using 3D data in the built environment has been to capture that data for extraction and design intent. With owner involvement, however, the data can maintain its value into the lifecycle of the building. The goal of the owner is to fully understand their facility, processes, and potential value-add opportunities.

Scale and growth become much more tangible and concrete when an owner can understand to incredible detail the condition of their assets. Many companies offer numerous products and house many complicated processes. With this data at their hands, change management and adaptation become easier and easier. When companies can throw the switch on product changes and adapt faster than competitors, they begin to gain a competitive advantage from such capabilities. Deployment of a “digital twin” in combination with a time or process perspective can leverage further advantages and create a much more liquid data flow.

This means the answer to “Who wants the data?” is changing, thus making “Who owns the data?” all the more important. With all this potential out there waiting to be extracted, let me offer a new analogy that perhaps better captures the “who owns the data?” dilemma: Photography.

Is Photography analogous to laser scanning?

Think about it: This data holds so much value because it has been refined with our intellectual property. These are confidential processes or workflows, new concepts or workarounds for common industry players. Similarly, photography may be on the surface a flashy visualization, but underneath is actually intellectual property. With photo rights, the ownership of the photo belongs to the person that physically presses the shutter.

When a wedding photographer is hired for a photoshoot, they are paid to take photos of the entire day or at an hourly rate, however it may be negotiated. But the photos are the property of the photographer. Of course, I could easily take the photos myself with my advanced smartphone, but we use photographers for occasions because of the hardware and experience that comes with a seasoned photographer.

When a wedding photographer is hired for a photoshoot, they are paid to take photos of the entire day or at an hourly rate, however it may be negotiated. But the photos are the property of the photographer. Of course, I could easily take the photos myself with my advanced smartphone, but we use photographers for occasions because of the hardware and experience that comes with a seasoned photographer.

Sure my new smartphone is great and is the newest model with the most up to date dual lens camera, but it does not compare to more robust cameras with varying lenses and other specifications. Similarly, I may take a great selfie, but my experience with lighting and composition would pale beside that of a professional photographer.

So, what am I paying for when I hire a photographer? Essentially, the payee is granted an unlimited license for use of the photos. According to several law sources, the employer only becomes the owner of the photos if the contract photographer uses your equipment and is on paid company time when capturing the photos.

Does reality capture data differ? If I laser scan your facility, do I own the data or do you? It is your property, so why would I, the scanner operator, own the data?

Well, according to intellectual property rights as understood in photography, the data would technically be owned by the company that captured the data. That’s me. Of course, contracts would be set into place for the owner or the designer to be granted an unlimited license to the data. No problem. But if you’re the owner of the facility, you most definitely do not want the data owned or bought by anyone else!

This brings us to another nuance involving intellectual property: Exclusivity. Photographers might look to showcase a great wedding photo for marketing or sales purposes, but if a client wishes to make these photos exclusive to them, that generally impacts the cost structure. So, if you, as an owner, look to capture existing facilities, unless you have the equipment and software to complete the task yourself, you will be negotiating with a capture company for an unlimited license to that data with exclusive rights to it.

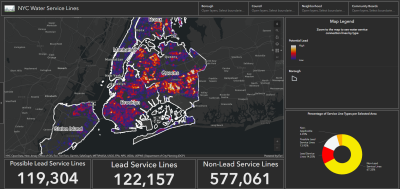

Of course, you might argue that most owners don’t want the data, anyway. They just want whatever the deliverable happens to be that was extracted from the data. They’re basically buying a print. But with the rise in popularity of digital twins, these data sets will need constant updating and the data will need to be accessed over and over again. Further, as the scans multiply, the size of the dataset quickly becomes an issue for consumers not easily equipped with the basic tools for storage and visualization.

Many in the industry utilize powerful resources to not only capture the data, but also to manipulate and extract value out of the data. For owners and asset managers looking to leverage these digital twins, the first step is to create a consumable format with which to comprehend the data.

Does this suggest a new laser-scan-data-as-a-service model?

Current methods to harness and extract the data are handled locally on specialized machines with technicians trained in the processes of doing this work. But the true value of the data is often found when sharing it between stakeholders for collaborative efforts. Clearly, when this data can be shared across design and construction teams, there are obvious benefits. The same can be said for the owner as they begin to study and extract data. Thus, one of the many developing fronts for reality capture data is deployment and access granted through some online platform to stream this data as it is captured and extracted.

The idea of hosting reality-capture data can be done in many ways, but may also create an even greyer area when determining ownership and data rights. To guarantee ownership of the data and access to it, facility owners could maybe create an internal hosting solution or intranet of sorts to ensure the data will be stored where it is intended as well as used as intended. But think of the IT lift for that!

The idea of hosting reality-capture data can be done in many ways, but may also create an even greyer area when determining ownership and data rights. To guarantee ownership of the data and access to it, facility owners could maybe create an internal hosting solution or intranet of sorts to ensure the data will be stored where it is intended as well as used as intended. But think of the IT lift for that!

One wonders if the future of reality capture is more subscription-based, like your Netflix account, rather than transactional, where you pay for a scanning job and never talk to the reality capture team again. The organization performing the scanning and extraction would own the data and the building owner would pay for continuing access to it, with the scanning organization providing further reality capture on some agreed-upon timetable.

Of course, this creates any number of further questions: Is a reality capture company going to have the expertise to create a cloud-based hosting solution for facility owners to access their data? And security is another grey area that many can become concerned over in this case. Is that reality capture company going to need to contract with yet another third party to ensure outside parties aren’t able to access the data for nefarious purposes? And will that third party then have access to the data?

It seems the questions surrounding the data’s ownership are as numerous as the potential uses for the data. One thing is for certain: As the benefits of having the data available increase for facility owners so will the focus on data ownership.