There’s nothing better for a burgeoning technology than for that technology to become a mandated piece of a larger process. To that end, I found a great article in Electric Light & Power from Paul Richardson of Network Mapping, advocating for airborne lidar as a compliance tool for the North American Reliability Council’s reliability standard FAC-003.

His argument, and it makes sense to me, is that if power companies are going to have to deliver a vegetation management plan for their powerlines, there aren’t many better and more efficient ways of documenting vegetation along the lines than airborne lidar.

Essentially, this FAC-003 works to avoid any vegetation-induced outages: vegetation growing into lines and interfering, or vegetation falling down onto the lines and knocking out power. The latter is something we know well here in New England, thanks to copious amounts of heavy snow knocking down tree branches left and right (one of the best things about heating with a wood stove? Power outages mean frying stuff up on the wood stove, which the kids get a kick out of).

So, FAC-003 forces power companies to come up with something called a TVMP (transmission vegetation management program), part of which is a schedule of rights-of-way inspections. As you might imagine, this has a fair number of transmission line owners freaking out – how do they go about inspecting miles and miles of right of way in any sort of efficient fashion?

Well, yeah, aerial lidar:

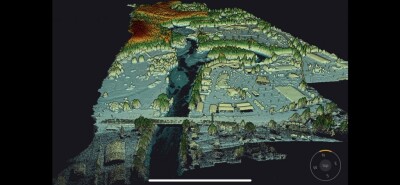

Aerial LiDAR technology has been applied extensively to electrical transmission capturing towers, conductors, vegetation and other objects within the right-of-way, as well as the terrain. An operator prepares the 3-D point cloud by classifying objects within the dataset. The classified dataset is used to build a 3-D engineering model of the line within PLS-CADD, including structural representations of the towers and conductors. The model is attributed with information pertinent to compliance with FAC-003. The line voltage is entered for each circuit together with the clearance distances required between the conductor and classified objects. The temperature of conductors for each span at the time of flight is calculated to IEEE standard 738 with in-flight meteorological data, ground weather station data and line load data. The conductors can be sagged to their maximum operating temperature and the infringement distances determined at this position. Weather cases can be defined so that vegetation clearance reports produced from the model include the effect of wind velocity on conductor blowout.

Richardson says he can typically survey 100km a day and since he’s in the air, terrain isn’t a problem. That all sounds great, right?

Well, GeoCue’s Lewis Graham does make the point that there might some push back from operators on utilizing lidar like this on a regular basis. He estimates the annual spend on lidar would have to be something like $675 million.

Still, that’s the power companies’ problem, not the surveyors’. For now, it represents a pretty sizable opportunity.