A recent partnership between GeoSLAM with Virginia Polytechnic Institute shows how reality capture and VR can take people back to experience the little-known story of mining warfare in World War One.

The community of Vauquois in North-East France was destroyed between 1915 and 1918 and much of the damage is still visible as a result of huge craters and dugouts. While the nearby Battle of Verdun, the longest of the First World War, features prominently in the history books, the little-known story of tunnel warfare is told through the battlefield of Vauquois. Throughout the four-year battle on the Western Front, French and German troops dug miles of tunnels under each side’s positions to plan explosive mines to ‘bomb’ the enemy from below. The Lantern Tower now marks the fallen at Vauquois, estimated to number more than 14,000 people.

The community of Vauquois in North-East France was destroyed between 1915 and 1918 and much of the damage is still visible as a result of huge craters and dugouts. While the nearby Battle of Verdun, the longest of the First World War, features prominently in the history books, the little-known story of tunnel warfare is told through the battlefield of Vauquois. Throughout the four-year battle on the Western Front, French and German troops dug miles of tunnels under each side’s positions to plan explosive mines to ‘bomb’ the enemy from below. The Lantern Tower now marks the fallen at Vauquois, estimated to number more than 14,000 people.

It is so difficult to imagine the horrors of living deep underground in wet, cramped and cold conditions for days at a time. For students and historians around the world who are learning about this event, it is not always possible to travel to France to crawl through the remnants of the tunnels and craters in person. To recreate an experience of the tunnels of Vauquois in the US, a group of researchers at Virginia Tech is bringing the battlefield to classrooms and museums, with the help of reality capture and virtual reality (VR) technology.

Capturing data underground

With support from a federal grant and combining a range of disciplines from across the university’s library and the Department of Visual Arts, the Visualizing History team first traveled to the area in 2016. For ten days, the team captured details of the terrain of the hillside battlefield. Progress was more challenging, however, when they attempted to scan inside the tunnels. The confined spaces meant that some areas were inaccessible with a terrestrial scanner and it was time-consuming to repeatedly set the device to scan multiple small areas.

Using GeoSLAM’s ZEB Horizon handheld laser scanner, which allows users to map indoor and outdoor areas in 3D at normal walking speed, the researchers were able to map the tunnels far quicker than with stationary laser scanners. Without the need for formal training, the team captured scan data inside the tunnels with the GeoSLAM unit more than three times faster than with a stationary scanner. As well as enabling speedier data collection, integrating the SLAM (simultaneous localization and mapping) device with GeoSLAM software enabled the data, which can be collected from a range of underground environments such as mines and tunnels, to be quickly processed into a point cloud. This process enabled the team to see where data was missing and collect it before leaving the site, helping to create a more complete and accurate virtual environment.

Creating an immersive experience

Back on the Virginia Tech campus, the team engaged the expertise of students and facilities from numerous departments including visual arts, history, education, computer science, mining engineering, and cinema to build a life-size model of a tunnel and generate the virtual environment of the battlefield. This allows students wearing VR headsets to ‘walk’ through the scene, experiencing it with both sight and touch.

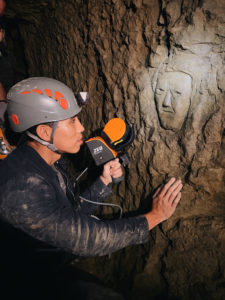

VR data processing can be extremely time-consuming, meaning that saving time collecting data in the field means that a more realistic and believable experience can be created. One example of this in the Virginia Tech project was the recreation of a face that was carved into a wall of one tunnel in Vauquois. The inclusion of this detail in the VR tunnels enables participants to combine the virtual world with a physical object, creating an immersive experience.