Geiger-mode and single-photon LiDAR have the potential to totally upend the business of airborne LiDAR collection.

They promise this disruption by collecting much faster (numbers reach as high as 30x the speed of traditional LiDAR) and in much greater density. This could make airborne LiDAR collection fast and affordable, so much so that we may be able to map very large areas on a frequency that approaches continuous capture. The implications for commercial work and even carbon-measurement are huge.

As a result, the technologies were the talk of the show at ILMF for the past two years running. As with any new technology, however, the initial excitement has faded and reality has set in: No tool is without its challenges.

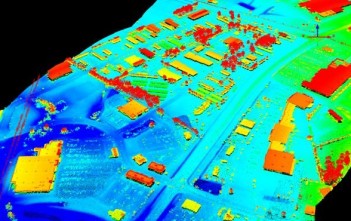

At ILMF 2016, the USGS presented the findings from their testing period for these new sensors. They found that the sensors performed well in areas of no vegetation, where they captured data that was extremely dense and well within USGS specification. In areas of dense vegetation, however, point density and vertical accuracy were cause for concern.

Fast forward to today and Sigma Space Corporation, the company that provided the single-photon sensor for USGS’ testing, has laid those concerns to rest.

In cooperation with the University of Maryland, the company has conducted and published a study showing that “3D forest structure and topography can be measured rapidly, efficiently, and accurately over large areas” using single-photon LiDAR.

(If you’re wondering how single-photon LiDAR works, I’ll refer you to UMD’s press release, which contains the simplest explanation I’ve seen anywhere.)

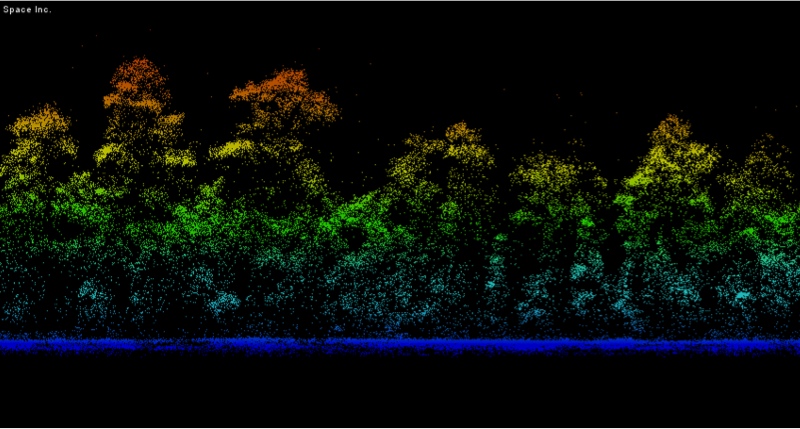

Sigma space single-photon data

The Test and the Results

The study was undertaken by Sigma Space in cooperation with the University of Maryland and funded by NASA. The results were posted in the Nature journal Scientific Reports.

A quick description: Scientists used a single-photon LiDAR sensor to map the entirety of Garrett County in Maryland, USA, which covers a total of 1700 square kilometers.

The challenges of single-photon LiDAR devices are laid out very clearly in the study.

Because these devices use the green wavelength, they are “not ideal for vegetation studies.” The green wavelength is sensitive to solar noise, which buries the signal, and “leaf-reflectance is much reduced” compared to the near-infrared wavelength used by other LiDAR instruments. Simply put, the data gathered by single-photon LiDAR in heavily vegetated areas is noisy.

Luckily, they found the data cleans up very nicely when you apply a noise filter.

After applying a “novel” noise filtering technique, they compared their single-photon data with field measurements and leaf-off single-photon data for the same areas. The results? Single-photon data was similar to traditional LiDAR but with higher point density and better structural detail.

The need for noise filtering raises new challenges. For instance, the researchers found that a high degree of calibration was needed for gathering effective data. This implies its own time and cost challenges.

“Nonetheless,” they write, the “efficiency of data collection, and its ability to produce fine-scale, three-dimensional structure over large areas quickly strings suggests that SPL should be considered as an efficient and potentially cost-effective alternative to existing lidar systems for large area mapping.”

There you have it.