How can experimenting with 3D laser scanners affect design/construction workflows?

LONDON—If you ask co-founders Matthew Shaw and William Trossell just what exactly is ScanLAB, you get a little bit of hemming and hawing. “We’re slowing becoming a fully fledged business,” Trossell says.

But why hurry? A couple years out of the Bartlett School of Architecture, at University College London, the pair are still in what you might call a research and development phase; the experimentation and exploration they’re doing on the possibilities of 3D laser scanning might lead them to a business model that hasn’t quite been invented yet.

Coming to laser scanning while at school – FARO had made available one of its Photons to the Bartlett – Shaw and Trossell were using the technology for small-scale objects, carving something out of wood, say, then scanning it so as to be able to work with it in Rhino.

“And then there was this realization moment,” Shaw remembers, “where I thought, it’s not just something that can happen with objects, it can happen with buildings and cities as well.”

Further, these small objects could be scanned and then become very much a part of those buildings and cities: “We’re speculating on where the line is drawn on those two things.”

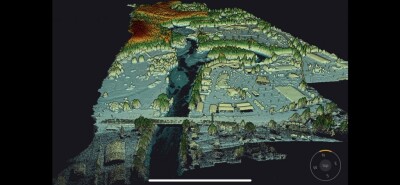

This has led to projects like the scanning of smoke and fog; the creation of objects that are invisible to scanners; the implanting of fake objects in real lidar data. Essentially the two are exploring the possibilities of real-world data capture.

But it’s not all experiment and wonder. ScanLAB have real ideas about how 3D laser scanning might benefit the architecture profession, which has traditionally resisted working with point clouds.

Combined with the fabrication techniques that are being introduced in architecture school now, laser scanning presents the possibility of taking the idea of the architect back to a very traditional idea of architect as master craftsman. “In a way,” says Trossell, “this is a way of giving architects back dominance over the final piece. Scanning is another way to take back some of the things the construction companies and builders have taken away.”

While Shaw acknowledges that architects have a desire to work in a precise and scripted world, “the ability to be working on such a perfect set of data,” such as a point cloud presents, “should provide many opportunities for architects, too. The idea of tolerance should be changed. It’s not a bad thing. It’s an opportunity to do some really amazing architecture.”

What can change with laser scanning?

Essentially, says Shaw, “3D scanning makes the real world and what’s in your computer much more harmonious with each other.” Architects can scan an area where something is to be built and have a completely accurate picture of the landscape in which to set a building, for example. Or “you can really test what you thought were going to build with what you actually built,” Shaw says. And that’s more important when you’re dealing with today’s ever more experimental digitally designed buildings that don’t always deal in straight lines and square corners.

Finally, not only does scanning empower the architect, but it also brings the architect closer to the construction firms and contractors, the ScanLAB pair say:

“The tension between the people who are actually building and the designers is always about the uncertainty of what’s going to get built,” Shaw says. “The construction company wants it to come in on budget, and if the digital designs are getting closer and closer to how this thing can actually be built, both sides will be happier. It’s easier to cost out and plan,” and therefore what gets built is more exactly what was designed in the first place.

So, where’s the business model?

“I’d love to be able to tell you where the money is and just how we position ourselves,” Trossell says, but they’re still beginning to line up clients and figure just what exactly their value proposition is. “We’re looking at many areas,” Trossell says. “It turns out that people want to buy some of what we’re doing as a piece of art, which is very interesting. I’m not sure many surveying companies look at what they’re doing and say, ‘Hey, that could go in the Tate, or MoMa.’”

“We’d like to be some of the first guys who have noticed this can be beautiful stuff as well as incredibly accurate,” Shaw agrees.

They won’t be the last to notice, though. Bartlett graduates and those from other architecture schools around the world are beginning to leave with the knowledge of software like Rhino and hardware like FARO tucked under their arms. The architects of tomorrow will be far more comfortable working in these kinds of digital formats.

Shaw seems to be speaking for a profession as a whole when he says, “It’s all sort of kicking off for us at the moment.”

If you’d like to continue the conversation, drop them a line at [email protected].

Also, see the recent write-up they got in Wired.