Angelo Beraldin, senior research officer at the NRC Institute for Information Technology in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, has worked on a catalog of projects that include archaeological and historical sites around the world. He and his staff of 15 have imaged works ranging from Palaeolithic figurines, Byzantine and early Christian crypts, medieval castles, and paintings by Renoir and Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa.

Beraldin says digital cultural heritage scanning “offers a challenging and high-visibility test bed for new technologies and concepts that will also be applicable to other sectors” including manufacturing, medicine, aerospace and forensics.

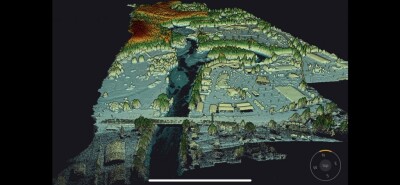

Culture heritage allows us to open up to the world,” Beraldin says. “[It’s] critical for the whole world. We need to understand other cultures, and 3D can bring a lot, especially those sites that have been closed to the public. 3D can bring a lot in terms of virtual visits assuming that you have very good models. … The 3D model by itself is not sufficient; you need also the historical [information]—whatever research has been done—in order to talk to the public. But you can also use it for scientific purposes (such as allowing scholars to interact in a virtual environment). For example, if you have a painted cave with ‘weird’ paintings (pictographs), … you can engage in discussion (with experts and the public). You will bring that information out in the open without damaging [the environment].”

Getting Intimate with History

Beraldin points out that 3D imaging technology helps cultural heritage projects by capturing views that are physically impossible to get because of the locale. It can also unveil techniques that better help us understand history. “You can create renderings that aren’t necessarily realistic that can contain other information [such as]shape information and superimpose infrared images,” he explains. “You can detach the color. You do it artificially with computer graphics tools.” For example, he says, his team was able to take all the colors out of the renowned Mona Lisa painting to see what lay beneath, such as minute marks and signs of paint layers. This analysis revealed that the painting has no brush strokes or fingerprints. Researchers can also evaluate the chisel marks of sculptures and the brush strokes of paintings. “We can only see the different shades in 3D. But to see a Renoir without color, the brush strokes are very prominent and thick,” he says. Now that’s some seriously smart data.

And the processing to output this data is right in line with the next generation of the workforce, Beraldin points out. 3D images can “create virtual reality theaters, which is not a bad idea if you look to the future. All the new generations that are used to video games can function in that world. Generations coming up will be more fluent in that area.” This is a possible hook to lure the future workforce.

Tools of the Preservation Trade

NRC’s equipment differs from the arsenal commercial customers use. While the hardware used is pretty standard, “The difference will come in the different patents we have on specific aspects of the technology,” Beraldin explains, estimating that the NRC has established 30 key patents that function by quality not weight. He describes one invention from the Renaissance that engages the triangulation system for scanning using a synchronized method. “Triangulation is typically a method that allows you to measure a point in space by intersecting two rays originating from two vantage points. The projection of light rays works equally well (e.g., laser). We measure at the different angles creating a triangle…. [then], in our laser scanner, we move (scan) the laser beam on the scene, and with a double-sided mirror, we track that motion with a sensor (like a camera). This is called the synchronized scanning approach. It has many, many advantages.

“We customize many things,” he continues. “This is part of the higher-risk R&D we do. We have to [develop custom software for many of our projects], especially for the massive amounts of data. For the Erechtheum project in Greece undertaken last year, Beraldin and his team had to develop their own algorithms to flow the project.

“People come to us with problems and culture heritage challenges [but]they’ve helped us develop and push the technology in different ways—the acquisition, processing, modeling, visualization of that information,” Beraldin says. Even with all of this processing and measuring, NRC always relies on 3D metrology. “It’s based on making sure we know what we’re measuring—communicate the quality of the data that’s being acquired—so we also have a very strong activity in 3D imaging metrology (not CMM). We don’t try to output data so it looks nice. Our business is measurement—the quality and the uncertainty of what you’re measuring.”

Such research serves as a foundation for industrial and other products and techniques. Beraldin says all categories of research and business utilizing 3D technologies is growing. “If you look at the lifecycle of technology, we’re just going up the curve,” Beraldin says. “We’re leading the pioneers and leading the enthusiasts.”

Future Captures

How might scanning improve for cultural preservation projects in the future? Beraldin eyes the industrial market as a development leader. “A lot of people working in that area (culture) work because they are subsidized,” he says. “It’s not easy to develop a business model for digital heritage projects. There’s not a lot of money available.

“And that’s where it’s frustrating for people in the field,” he continues. “We can put a system on a shuttle, but why can’t I put a system in several museums? Why can’t I have a system that’s the same price as a digital camera with the same quality of the system on the shuttle? We’re still not there yet, but I’m sure in the future, once all these new features appear on the industrial systems, people in cultural heritage will benefit from that because a lot of the investment would have been paid off. And people will be able to benefit from reduced cost. It will also be easier to use—you won’t need a PhD in computer vision to use a system.”

Overall, Beraldin sees the very positive impact of 3D laser scanning and imaging for the cultural/digital heritage sector. “Culture heritage is a way to demonstrate the technology,” Beraldin says, adding that you can publish data from such projects while you can’t with forensic projects.

Learn More about Cultural Heritage Scanning

Beraldin and others will present on their experiences scanning cultural heritage sites and objects at SPAR 2009 this March in Denver. To register, visit http://www.sparllc.com/spar2009.php.