As the Irish converted to Christianity in the fifth century, Saint Patrick created scores of monasteries with scriptoriums, where ancient books were painstakingly copied in florid detail by monks who often didn’t know the language they were copying. In this way, many of the great classics of Western literature were preserved during Europe’s Dark Ages.

Copying something to preserve it for future generations, and to gain more understanding of it, is a common practice of artists and writers, which has helped save many masterpieces. But the practice has gained added relevance in this three-dimensional Digital Age, due to the recent blaze that partly destroyed France’s historic Notre Dame Cathedral.

Built in the thirteenth century, Notre Dame is a Gothic masterpiece that has been altered repeatedly over the centuries. But despite the alterations, as well as many wars and changes in political leadership in France, the Paris church has survived as a beautiful, storied testament to the style and resilience of the French people.

Like an aged document with unclear origins and dubious authors, the cathedral’s architectural design, and its construction materials and techniques, are still being figured out by historians. Of such stuff, the wonky careers of historians are made. And thanks to computers and one dogged academic who died in November 2018, what is permanently gone, lives on in a 3D model.

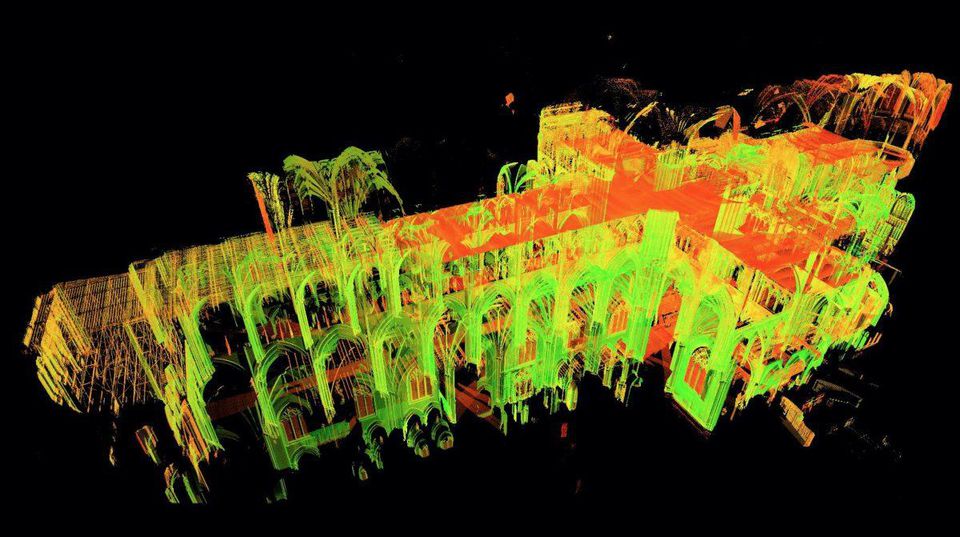

Obsession, passion, preoccupation—call it what you will, the efforts of Vassar College professor Andrew Tallon have helped preserve details of Notre Dame Cathedral that would’ve been lost to history, without him. In 2015, Tallon’s passion for Notre Dame led him to painstakingly create a 1-billion-point 3D model of the cathedral. It also led him to be a co-founder of the American charity, Friends of Notre Dame.

Obsession, passion, preoccupation—call it what you will, the efforts of Vassar College professor Andrew Tallon have helped preserve details of Notre Dame Cathedral that would’ve been lost to history, without him. In 2015, Tallon’s passion for Notre Dame led him to painstakingly create a 1-billion-point 3D model of the cathedral. It also led him to be a co-founder of the American charity, Friends of Notre Dame.

In a 2015 video on his documentation process, which was filmed at Washington’s National Cathedral, Tallon talks about how he documented such great buildings, and why he did it.

“I’ve been interested in the way Gothic buildings stand up, and the way they handle themselves structurally. And unfortunately for me, there’s nothing written about it. Masons never stopped at the end of the day and said, ‘I built my cathedral this way because…,’” Tallon says in the video. “And so, I’ve been using more sophisticated technologies these days to try to get new answers from the buildings. The best technology to solve problems like this is the laser scanner.”

The late Associate Professor of Art for Vassar College’s research has been showcased on the PBS production Building the Great Cathedrals, on Arte TV’s documentary Les cathédrales dévoilées , and on National Geographic’s Innovators series and on other programs.

His teaching focus was on medieval architecture and art, as well as on pre-modern acoustics. Though this expertise may seem arcane to the average layman, such architecture and art is studied partly to understand how it works. Now, his billion-point map will be studied alongside ancient blueprints and other documents, as Notre Dame Cathedral is rebuilt. And the French are keen to rebuild it, as soon as possible.

With the ashes of part of the famed cathedral practically still smoking, Paris’s mayor and business leaders called for the immediate repair of the historic structure, which prior to the fire had been recognized as needing extensive restoration. Tens of millions already have been pledged by corporations giving to the effort.

And Tallon’s map of Notre Dame, created by using a billion points measured by lasers, is now part of the current historical record. With its use in the rebuilding of the great cathedral, that map will be part of the new historical record of a church that has outlasted kings, emperors, wars and catastrophes.