Phil Manning uses the newest technology to investigate the oldest stuff

MANCHESTER, UK – When I finally get in contact with Phil Manning, he’s Skyping me from a room that’s part of a $5 million CT (computer tomography) scanning unit that has recently been installed, giving him access to half a dozen CT bays here at the University of Manchester, where he heads the Palaeontology Research Group.

“Some of these I could literally sit inside and do a full body scan,” he says, clearly pretty excited, “which might not be very healthy, but it’s astounding X-ray micro tomography.”

Manning might spend most of his days discovering new truths about some of the oldest things to have walked the Earth, but he spends the rest of his time looking for new technology that will help him with that pursuit. “I tend to work with objects and machines that are not exactly off the shelf solutions,” he says, “and that can have huge implications for developing new areas for ideas for solving imaging problems.”

His interest in 3D goes all the way back to high school, he says, where he was something of an artist. “I realized that 2D art was really restrictive,” Manning says, “and 3D gave you so many more options. And very often, when you’re looking at art in books, and it’s 3D art they’re trying to depict, you’re screwed! You’ve got an inherently 3D form represented in only two dimensions.”

Sound like any industrial facilities or crime scenes you know of? You think those sorts of places are hard to model?

“Fossils are a compete pain in the ass,” Manning says with a laugh. “They’re heavily mineralized; there’s just a whiff of organic material; and picking out what’s original to that animal is bloody hard.”

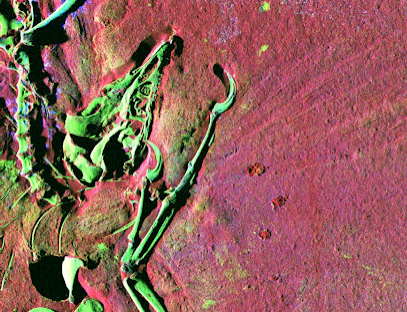

Hence his pursuit of the newest and most cutting-edge 3D imaging technologies, including airborne lidar and terrestrial laser scanning and just about anything he can get his hands on. The newest of those technologies includes the use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, where Manning was working earlier this year and to which Manchester has been granted two more years of access, which allows one to look at a 3D model of just a single chemical element as a subsection of whatever object it is you’re examining.

“When you’re working with a synchrotron,” Manning explains, “you can finely tune the energy of the [X-ray] beam just below the excitation energy of a particular element.” For example, if you did that to a human, and tuned for iron (again, not necessarily a safe thing to try), you’d largely get a 3D model of the pulmonary system, since iron is concentrated in our blood.

“Now, we can do that with any material,” Manning says. “That’s the new grail of tomographic imaging.”

And, yes, all of this is just as expensive as it sounds. Manning knows what you’re wondering: “Why the hell should I be funding all of this? Who cares what T-Rex was thinking?”

That would be exactly the question you’d want to ask if you’d like to get Manning up on his soapbox.

“The pivotal thing with our research,” he says, “which I think makes it more than relevant to society today, is that we are treating the fossil record as the longest experiment ever done. These things have been buried in the ground for 600 million years and now we can review what happens to those objects once they’re buried in the ground.”

Can you tell your grandchildren with confidence what will happen to those things you’re burying at your local landfill 100 years from now? One thousand years from now?

“I’m afraid if you want to set that experiment up,” Manning says, “you’ll be long dead before that experiment ends. The research we’re doing helps us understand the mass transfer of elements and compounds within the environment.”

“When I talk about everything from 3D tomography to the elementary inventories of animals,” he continues, “it’s of critical importance for people today in the assessment of risk when they’re putting something in the ground that has the potential to affect and impact populations in the future.”

And 3D imaging is vital to Manning’s pursuit. “The absolute beauty of this,” he says, “is that we’re working from angstrom right up to the planetary scale, and we’re always trying to incorporate it into the 3D framework and that’s what’s providing so many robust arguments coming out of the research.”

In the end, Manning said, 3D is vital to uncovering the truth, which is any investigator’s aim. By way of illustration, he quotes Mark Twain: “There is something fascinating about science. One gets such wholesale returns of conjecture out of such a trifling investment of fact.”

“I want as much fact available to me as possible when I draw conclusions,” Manning says.

Hear Dr. Philip Manning speak on “Dinosaurs, Space Shuttles, and Synchrotrons” at SPAR International, in Houston, April 15-18. Follow his work on his blog at http://dinosaursabbatical.blogspot.com/.