As SPAR 2011, Parsons outlines the case for 3D imaging and historic preservation

HOUSTON—There is a tendency, maybe, to view the use of laser scanning and 3D imaging for historic preservation as purely of a philanthropic nature. But for Ruth Parsons, CEO of Historic Scotland and Director for Culture and Digital for Scottish Government, it has had any number of positive effects that go well beyond documenting history for the ages.

“We were an agency that was regarded as a dusty sleepy hollow,” Parsons told the crowd here at SPAR International 2011, as part of her keynote address. “Now we’re regarded as innovators and creators. [Laser scanning] has helped us articulate much more clearly how we contribute to economic growth.”

Though Historic Scotland manages 78 sites that are open to the public (and many more that are not), generating some 27 million pounds and, for example, allowing them to be the largest employer of stone masons in the UK, the organization started small in 3D imaging: the skull of a 14th-century knight.

By scanning the individual pieces and reconstructing the skull digitally, “we found the horrible knife wound on the head didn’t kill him,” said Parsons, “it was the pike in the middle of the face.” The discovery led to a BBC feature and public interest that, in turn, led to more interest in the work of Historic Scotland as a whole. And that’s good for business.

Soon, the organization found it could scan objects and rapid prototype them, generating income through the sale of trinkets.

Then there is Rosslyn Chapel, the first large indoor project Historic Scotland undertook. The building is particularly famous because of a Dan Brown novel positing that it is the home of Holy Grail. Thus, the scanning and resultant 3D models proved doubly useful: On the one hand, Time Magazine was motivated to run the colored point cloud and lend valuable publicity; on the other hand, a crazed fan took an axe to one of the pillars, convinced he would find the Grail.”

“That’s how important it is to get the data and document the critically important and beautiful sites,” Parsons said. “So that whatever happens, we’ll have that information and give access to people across the world.”

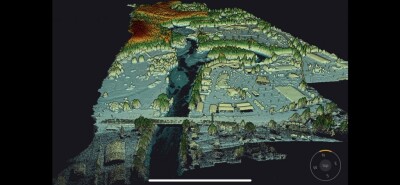

Next up was Stirling Castle, which Historic Scotland is restoring to how it looked in the 1540s as part of a 12 million pound project. It was “very difficult to actually scan,” Parsons said, “but it delivers value to us. At the Chapel, the value is in providing access and the historic environment encourages heritage tourism. But Stirling is a practical application. [The laser scanning] actually helps us with our conservation work. It’s an objective point cloud that gives just so much information that we can use to make the building more efficient and save money.”

For example, she said, instead of erecting scaffolding to do measurements and make decisions about work that needs to be done—scaffolding that then stays in place for months while the repairs are organized and prepared—Historic Scotland can now just use the scans to do that inspection and only raise the scaffolding when work is ready to be done.

Further, “we need to reduce carbon consumption by 40 percent by 2020, so this is a huge help in understanding how to do that,” she said. They’ll also be integrating thermal imaging into to the Castle models.

Finally, Historic Scotland was emboldened to embark on their most ambitious project to date: the Scottish 10, a plan to scan five very different historic sites in Scotland along with five World Heritage sites, starting with Mount Rushmore in the United States in collaboration with Cyark.

In this case, laser scanning has helped bring Scotland into the world’s eye, and has helped the country as a whole establish relationships with world governments as diverse as the United States, India, China, and Japan. “Each country is a key partner for Scotland,” Parsons said.

Further, the project helps to drive the Scottish economy, as some of the technology partners, like immersive imaging solution maker 360 Tactical VR, which that will help with virtual modeling on the Scottish 10 project, are based right in Scotland.

“Scotland is a small, small country, but we do love to punch above our weight,” Parsons said.