The Costa Concordia made headlines around the world when it ran aground in January after some ill-advised showboating by the ship’s captain. What many people following the story of the luxury cruise liner’s calamity did not know was the important role that 3D data capture played in the rescue efforts. This hidden “tale of an (extra)ordinary day of survey” was revealed by Marco Bacchiochi, Application Specialist – 3D Imaging Products, Codevintec, in a presentation he gave at the Optech Terrestrial Laser Scanning Users’ Meeting in Nice last week.

Bacchiochi explained that Codevintec was called in by the Italian Fire Brigade, which managed the initial intervention, to provide know-how on a broad range of (terrestrial and seaborne) surveying methods that would be used to give a complete overview of the site of the incident. The emergency response team was particular keen to know exactly what the Costa Concordia was resting on, as there were fears it might move during the rescue operation.

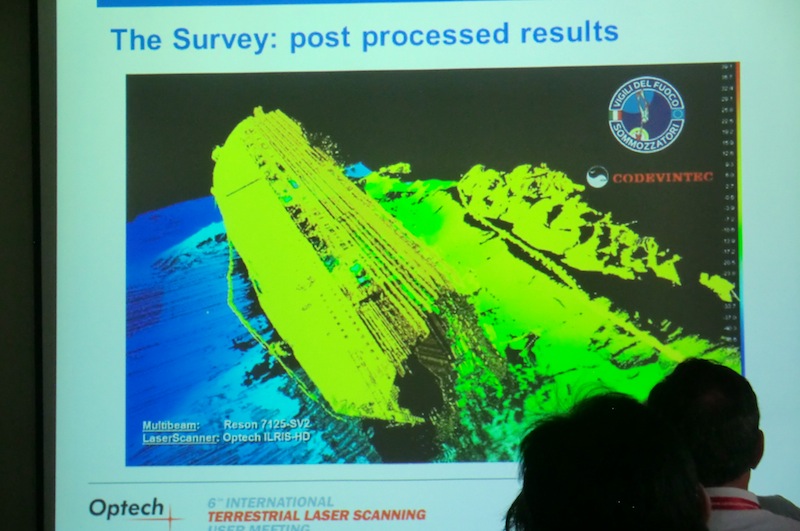

In addition to a Reson multibeam echosounder and a PSS Orion position and altitude measurement system, Codevintec brought in its Optech ILRIS terrestrial lidar unit to collect data on the part of the ship visible above the waterline. The lidar and bathymetric data were processed using Reson PDS2000 software to produce a working 3D model of the scene of the shipwreck.

The survey instruments were installed on the Milan Fire Brigade’s research vessel Nereide and, following some calibration and synchronisation checks, scanning began at 10:00 a.m. By 3 p.m., the results were being shown to the crisis team, illustrating the speed with which useful lidar data can be made available in an emergency response situation.

“It was really amazing,” said Bacchiochi.

Of course, it wasn’t – excuse the pun – all plain-sailing. On the multibeam front, the flat metal hull of the stricken cruise liner acted as a mirror to the acoustic waves, which required the use of the instrument’s FlexMode to get a quality result. Also there was a problem synchronising the laser scanner and motion sensor, which could not be solved in the available time window. “It wasn’t so dramatic, but we could see a little noise in the survey,” explained Bacchiochi. In addition, because of the 40-degree field of view of the ILRIS and the limited space between the shore and the Costa Concordia, it was not possible to scan all of the ship’s body from the Nereide. Thus the ILRIS was positioned onshore for a static scan that captured the missing parts and enabled a complete 3D model of the Costa Concordia wreck site to be generated.

Despite a few minor blips, the net result was a fast and accurate survey that provided vital information about the seabed and status of the sinking ship and which was greatly appreciated by the emergency workers. As Bacchiochi pointed out, “before the survey, no information was available on where the ship was laying. The crisis team was impressed by the possibility of seeing the vessel and its surrounding area from different points of view. Subsequent scans were used to monitor not only the wreck’s movement but also its deformation.”

All in all, a great example of what is involved in carrying out a very quick survey using different 3D sensor technology.