Academics say online 3D repositories created through scanning are “transformative science,” could represent fast-growing market

POCATELLO, Idaho—A collaboration between Idaho State University and Canadian Museum of Civilization researchers to further create an online, interactive, virtual museum of northern animal bones has been bolstered by a $1,029,232 grant from the U.S. National Science Foundation, announced last week.

Their efforts to scan rare specimens, put the 3D models online, and allow the world to explore and analyze their collections represents the “democratization of science,” said Corey Schou, Ph.D., professor of information systems at ISU and one of the principal investigators on the grant. “A 12-year-old can manipulate and play with the same bones as the top scientist in the world does in his lab. There are images that we’re going to have in this collection where there are only one or two known specimens in the whole world. And we’ll have them together in a single collection that everyone can share.”

How do they get from the real world to the digital? For years, Schou, who plays the role of “IT guy,” has been working with fellow grant principals Herbert Maschner, ISU anthropology research professor, director of the ISU Center for Archaeology, Materials, and Applied Spectroscopy and interim director of the Idaho Museum of Natural History; and Matthew Betts, Ph.D., curator of Atlantic Provinces Archaeology at the Canadian Museum of Civilization and a former postdoctoral researcher at ISU.

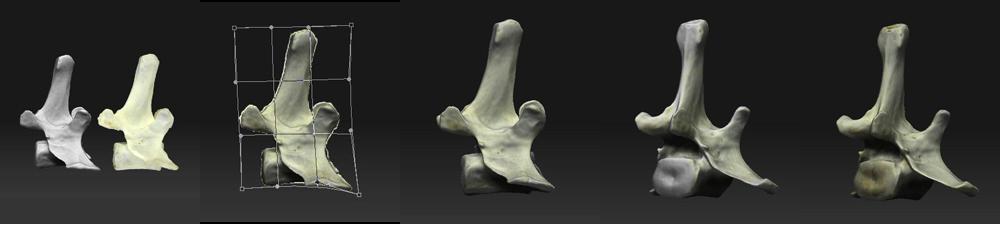

They started with a $310,000 NSF grant received in 2008 to begin creating an online two- and three-dimensional archeological collection of Arctic animal bones, which was built using techniques developed in the Informatics Research Institute and the Idaho Virtualization Laboratory. The VZAP team has now produced more than 3,000 individual 3D models and more than 12,000 digital photographs, while also developing advanced 3D laser scanning protocols, implementing a robust database, and creating a revolutionary graphical user interface, the Dynamic Image Engine.

They’ve been making do with NextEngine 3D scanners, but have recently been experimenting with medical-grade CT scanning and will, with the grant, purchase a higher end Minolta scanner.

“Speed of scanning is a limitation” right now, said Betts. For the first phase of the project that’s being continued with the $1 million grant, “we proposed scanning 132 [species],” but, because of the tedious nature of scanning the bones and then stitching on digital photographs to the 3D wire frames, “we reduced that to about 50. And we limited the number of bones we scanned.” Also, he said, “for very small objects, like fish and birds, the scan time was greatly increased. The edges were sometimes less than a millimeter wide, so the accuracy was of paramount importance.”

“The new Minolta should increase our productivity four-fold,” said Maschner. He’s aware of more expensive options that cold eliminate the need to stitch on the digital photos to get the color likenesses of the bones, “but no academic could ever afford it,” he said.

As for the CT scanners, which they’ll continue to use thanks to a collaboration with a nearby medical facility, “we’re down to 10 microns of accuracy,” Betts said, “and they’re very rapid.”

All three researches believe they’re paving the way for a rapid increase of collection holders – museums, academic research facilities, historical societies – scanning in their holdings and making them available to the world at large in 3D and over the web.

“It’s absolutely starting to be an explosion,” Betts said. “We’re right on the leading edge of digitizing collections and making them available online … You can either do photographs or 3D models, and no one is doing 3D at the scale that we’re doing it. We’re trying to do it for the entire North American Arctic. The web technology that we’re developing as well, we’re hoping it can be used as a model to apply to other collections’ problems and get it out there for people to use.”

The applications for education are obvious, with first-graders all the way through post-docs having a need to examine rare specimens in a 3D environment, but Maschner gives a very pointed explanation of this permanent 3D collection’s benefit:

“I work in the Aleutian islands,” he said, on a swath of land that’s owned by lots of people — tribes, the government – and all these thousands of artifacts that Maschner has collected will have to be returned to a variety of different owners. “No one will be able to study this as a collection again,” he said, “so this is an opportunity to create a total repository for anyone to do the analysis without having to go to four different villages. That was the ‘ah ha’ moment for me.”