Laser scanning to help shipping firms manage ballast water regulations

BARRY, SOUTH WALES, UK – When ships take on ballast, they take on more than water. They also take on any number of marine organisms that hitch along for the ride. It’s how Alligatorweed hitched a ride from South America to Alabama. And how Purple Loosestrife came on over from Eurasia.

The problem is such that the international community has responded with diverse rules and regulations about ballast handling, including proposed global regulations put out by the International Maritime Organization and, in some cases, even stricter regional regulations like those put out by the state of California. Essentially, you’ve got to kill off all marine life living in your ballast before you expel it.

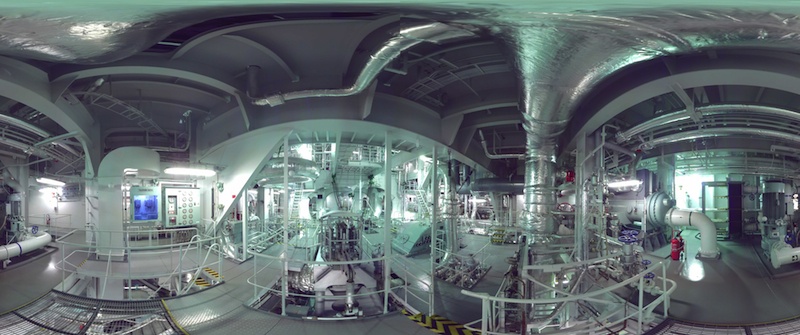

What all of this means is that practically all ships, around 60,000 of them, that travel the world need ballast water treatment systems, which are generally installed in and around the engine room, where space is tight. You can imagine the workflow the naval architecture team at Harris Pye, a global player in the offshore oil and gas, industrial and marine industries, had to go through as they proposed solutions for clients: pick out a potential system to solve the problem, measure potential spots in the ship’s engine room, put together a plan, make a presentation to the client.

Then the client says, “Is there a less expensive option?” Do that all over again.

Enter 3D laser scanning. “We do quite a lot of work offshore,” said Chris David, group technical director at Harris Pye, “where it’s quite difficult to survey.” Oil companies started providing CAD diagrams that resulted from laser scans from which Harris Pye could fabricate.

“We made the equipment from those AutoCAD diagrams and it just fit perfect,” David said. “We said to ourselves, ‘We can do one of these.’”

“We decided it was worth going down the road of purchasing our own scanner,” David said, considering the flexibility the company would gain vs. using a scanning service provider, and the utility of the scanner across much of the larger organization. “It was a bit of a step, I will say,” David said, “but we’ve got qualified people working for us, and when you look at employing a third party, we’d be bringing in someone to do a scan of an engine room without knowing what they’re scanning for.”

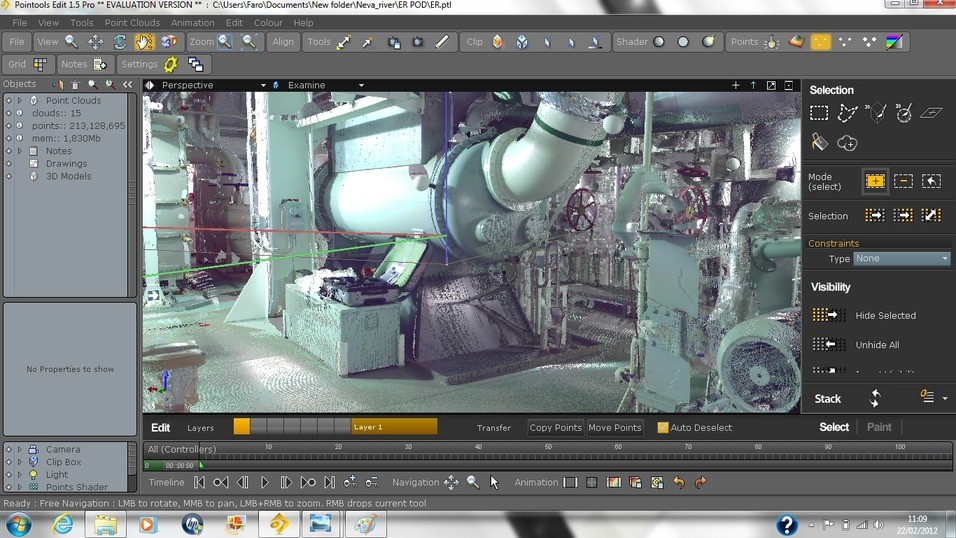

Harris Pye purchased a Faro Focus 3D roughly four months ago and created a workflow that involves scanning with the Faro and using the accompanying Scene software for registration. Then, said head naval architect Bolaji Bamowo, the company brings the point cloud into Leica’s Cyclone product, which can convert the data with its CloudWorx running in CADWorx P&ID Professional. Thermal stress analysis and flow design is done using Caesar II, and Staad pro is used to undertake structural stress analysis. They also use Pointools for visualization and taking measurements.

Even with that bit of rigmarole, “It’s very, very good,” Bamowo said of the resulting data and its utility. “We have all that data at hand – we’re able to make our own 3D model and check for clashes. Then, when we see that everything is okay, it goes a long way toward our confidence as we move into fabrication and getting everything installed.”

“You can imagine what the engine room looks like,” agreed David. “First, you have to pick the most likely area for installation, and if you don’t know what system you’re putting in, there might be three different areas you have to examine.” Previously, they’d have taken photographs, some measurements, taken the ship’s drawings, “and there would have been a lot of time involved with that.”

Then what happens if, as actually happened recently, one of the ballast water treatment systems being considered is taken off the market and a new one introduced after you’ve been on site? It isn’t all that easy to get back on the ship, which might only be in port twice a month and might be half way around the world.

“Now we can do a 3D walk around the engine room without actually being there,” Bamowo said. “And you can start to think outside the box, as well. You can come up behind someone working on the model and say, ‘how about we try this,’ because it doesn’t take any time to change it.”

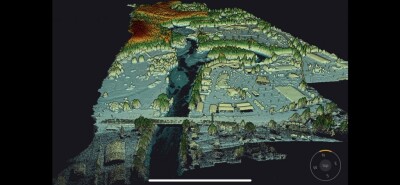

Everything worked as planned when scanning the engine room of the Neva River, for example, the LNG carrier of “K” Line LNG Shipping (UK) Ltd., from pre-ballast water system CAD design, through to system selection and installation. The scanning itself took about eight hours, David said, and the CAD modeling was done in roughly two weeks.

“It’s a wonderful tool,” Bamowo said of the laser scanning and 3D modeling. “It’s a wonderful tool, really.”

“It really is a time saver,” David agreed.