Using 3D data capture to preserve natural resources (and get in some beach time)

We’ve written before about the use of 3D imaging to map and manage natural resources: From identifying potential sites of rockfalls and predicting their future occurrence to assessing levels of forest cover for climate change mitigation programmes, laser scanning and photogrammetry providers are certainly finding plenty of interest.

Beaches are another natural resource offering potential business opportunities, particularly as more and more people in the US and Europe seek to live out their dreams of sun-fuelled, boardwalk existence in warmer climes. High-end artificial island developments such as The World in Dubai and The Pearl in Qatar certainly promise a lifestyle that plenty of people would like to enjoy. Making sure the reality matches the real estate brochure is another story, and that’s where laser scanning can come in very handy, as Morten Helleman of COWI explained in the “3D Imaging for Natural Resources” session at SPAR Europe earlier this month.

The Danish company, a specialist in aerial, terrestrial and mobile scanning, was called in by the Qatari authorities to carry out a coastal geomorphology survey of The Pearl after it had been noticed that sand was disappearing from some of the development’s beaches, shortly after the first investors began moving in in 2009. The goal of COWI’s survey – actually two surveys, a reference one in 2009, followed by a second pass in January 2011 – was to deliver reliable data for the further analysis of sand movement at 10 beaches where the sand had been shifting. As well as the digital terrain model, COWI also provided TruView solutions showing the point cloud and 360o panoramic photos.

The area was too small for aerial scanning, so for four days Helleman and his colleagues had the task of terrestrial scanning the relevant beaches in 90 degrees Farenheit heat beneath a beautiful azure sky (it’s a tough life!). At the end, they had produced what was needed: hard data that would allow the geomorphologists to calculate if the sand was disappearing out to sea or if it was moving somewhere else along the coast; information that would enable the people behind The Pearl to take appropriate steps to ensure the development lived up to its promises of glorious beach life.

Aside from the fabulous location, the details of the scanning process were fascinating, particularly as small sinkholes just offshore meant the guys doing the work could suddenly end up waist-deep in the ocean if they weren’t careful! “Using four target points for each scan meant we didn’t need field notes,” explained Helleman. He also noted that the scanning process would be much quicker today thanks to advances in the technology available. “Now we would probably use mobile mapping,” he concluded.

Some pretty neat 3D developments are also occurring in the field of geology. At SPAR Europe, Julian Trick from the British Geological Survey (BGS) demonstrated GeoVisionary, a ‘virtual field reconnaissance’ tool for geological exploration and mapping that greatly speeds up the interpretation of data prior to fieldwork (“from most of the summer to a couple of weeks,” he explained).

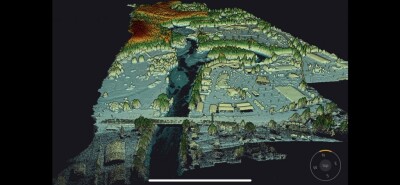

Developed for BGS by Virtalis, GeoVisionary offers an enhanced user-friendly environment that adds value to fieldwork by enabling the seamless visualization of data in an immersive 3D landscape. Its virtual geological toolkit “enables geoscientists to analyze and interpret data in a real-time environment,” commented Trick. Datasets are drawn from a range of geographical information system sources, including digital terrain models, digital geological maps, aerial photos, Landsat images, and topographic, geochemical and geophysical surveys.

GeoVisionary has already been used not only to integrate data from geological surveys and old Soviet-era maps in a potential oil field in southern Tajikistan, but for direct interpretation of scientific data from Mars in a 3D environment, or what Trick called “the ultimate virtual fieldwork.” From a SPAR reader’s point of view, perhaps what is most interesting is what will happen next: a new version of GeoVisionary incorporating point cloud data will be available “early next year,” according to Trick. “This will be useful for measuring rockfalls, for example,” he added. Other ongoing upgrades to GeoVisionary will focus on voxels, volumetrics and time-based data. All very exciting stuff, but what I really wanted to know was “what’s it like to hold a meeting at work where everyone is wearing 3D glasses?”

Trick laughed: “It was pretty funny to see at first, but we are getting used to it.”