One wouldn’t get much in the way of pushback if they were to suggest that collecting geospatial data is more accessible than ever, not only in terms of acquiring the tools necessary for these projects, but in the sheer number of methods which can be used to do the collecting. Much of this has come in the form of new autonomous systems entering the market – and older ones becoming, again, more accessible – most notably for our purposes with drones. That it’s easier to collect this data for a broader range of use cases than ever before in turn has placed increased demand on collecting it, with more organizations viewing it as a worthwhile endeavor than ever before.

This without question is a good thing for the industry, and really the world as a whole, as more information is rarely a bad thing. It has also gotten me thinking, though, about the weird place the industry currently occupies with all of these great, new tools, but lacking a workforce which has been meaningfully trained with them. Obviously that’s unavoidable with a new tool; you can’t be trained on technology that does not yet exist. However, as time goes on it’s become clear that these workflows are here to stay, and thus it makes sense to have more of this training happening at younger ages in school settings, ensuring future professionals have the skills needed as soon as they’re ready to enter the workforce.

With this in mind, one can understand why it caught my attention when I first heard about the Land.Air.Sea.Robotics (LASR) program at Johns Hopkins, part of which involves this data collection and understanding not just how to use the hardware, but how to pick which softwares to use in order to maximize the value you can get from collected data. Dr. Jim Blanchard is the instructor of two courses as a part of this program, and he took some time to speak with Geo Week News about his work and the state of this type of education in the United States.

Dr. Blanchard is uniquely qualified to talk about this, having worked in aviation, engineering, and education over his career. In high school, he enlisted in the Navy, where he first made connections which would eventually lead to his initial foray into drones. After leaving the Navy, he was a commercial pilot before a long career spent at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University. Then in 2013, he started to build curricula for the Department of Education to teach how to fly drones, using funding through colleges that wanted to put robotics into their STEM programs. That’s led to today as he is working with Johns Hopkins in a graduate program while also continuing to help develop similar programs for undergraduate studies, community college programs, and even in high schools.

How the classes work

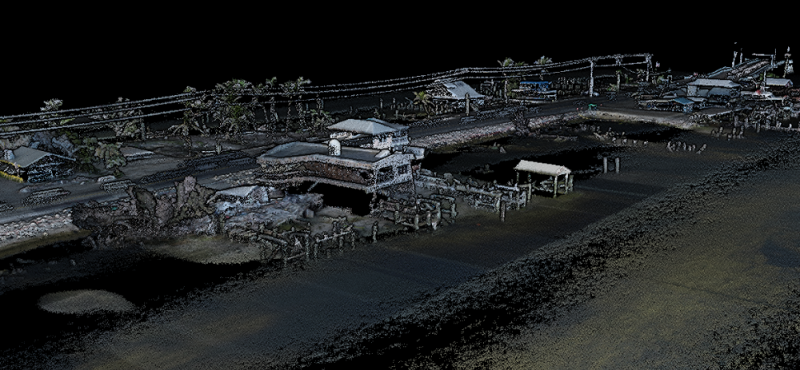

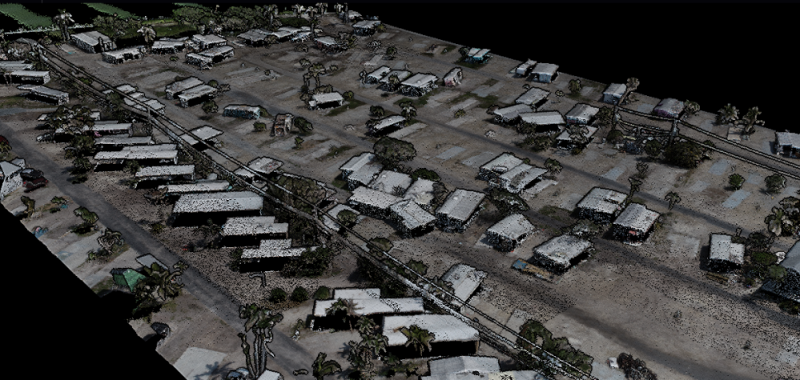

Dr. Blanchard explains that his classes are capped at 16 students, and while they come from all over the world there are periods in which they are all in-person at Johns Hopkins’ Washington D.C. campus, as part of the overall program’s requirements includes needing to spend a portion of one’s graduate years on campus. He further explains that the data collection class - largely focused on drones, though he also works with terrestrial and aquatic uncrewed systems - is generally broken into thirds. Students begin learning how to fly drones in preparation for to receive their drone pilot license. From there, students learn how to collect data and how to determine the best way to complete a particular project in terms of which sensors to use, and finally learn how to process and analyze the data through relevant software.

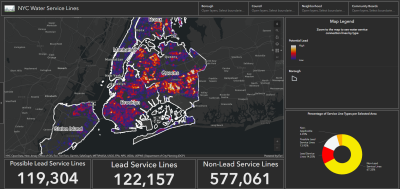

That last piece is really the critical one here at the graduate student level, and the part that at least in theory should be the piece that sets up students to take advantage of the data collection improvements mentioned at the top. As Blanchard tells us, while flying a drone does take training, it’s not an overly intensive process. The more difficult part is knowing all of the different sensors – and he notes that if you can think of a type of sensor, they’re teaching about and using them in his courses – and how to gain actionable insights from the data. For this, he leans on Esri products like SiteScan and ArcGIS as a whole for students to learn how to truly harness this information. He says, “At a minimum, students have to demonstrate a mastery of ArcGIS, layering, and georeferencing, and they have to do at least one image classification through the GIS image tools.”

Who are the students?

Heading into our conversation, one of the aspects that was the most interesting was simply: Who is taking these classes? It’s an interesting thought for two reasons, one being who is recognizing themselves as a fit in this growing field, and two being what paths forward they see for themselves. In our conversation, Dr. Blanchard notes multiple times that these are working professionals, so not necessarily young people who are looking for their first career. Instead, he describes a disparate group, though many with some drone or aviation experience, whether it be from the military or law enforcement.

Most notable, though, is the group of students who are in the program for environmental sciences or environment policy, a group Dr. Blanchard says is “probably two-thirds of everybody who takes his course.” While not much of a surprise, it is a notable piece of information to me. For one thing, it’s clear that anything relating to the environment is going to be at the forefront of, well, everything moving forward. It's the focus of the entire global society, and resources will only continue to be poured into the space. Furthermore, it’s an acknowledgement of how important geospatial is going to be in this fight. Those of us in the industry already realize this, of course, but these types of programs attracting people from that space is (hopefully) an indicator that this impact is recognized more widely as well.

What’s next?

As mentioned, Dr. Blanchard has more experience in the education space than just his work with Johns Hopkins, giving him insight into how this space is developing more broadly. After discussing his specific courses at Johns Hopkins, we also discussed how widespread this kind of education is, and he had really interesting views on this. Specifically, he does envision these types of programs becoming more commonplace moving forward, and perhaps most interestingly talks about how programs can be implemented in high schools and community colleges. These would be more focused on learning to actually fly the drones than the intricacies of data collection, but it forms a foundation for those later years of education that can lead to time in the field coming more quickly.

Most importantly, he says that any school looking to implement these programs will need a “champion,” someone who will take the program under their wing and allow it to flourish. In high schools, he says they need to be dedicated to this field, likening it to the job of a woodshop teacher. “You can’t be a math teacher and then go to the next period and do woodshop. It’s too dangerous.”

Overall, it’s clear this space is moving forward at a rapid pace, and we’re seeing that reflected in both programs being offered by colleges and universities around the country as well as students seeking out these programs. Says Dr. Blanchard, “To me, it looks like what we saw in the late 1980s when we had the internet boom going on. In the early 1990s, you could get a job if you had some college education – even if you didn’t earn a degree. They wanted to see the list of software applications you knew how to use.” We’re in a similar place now in geospatial data collection, and it’s about ensuring future professionals have as much in their toolbox as possible when starting to work in the field.