In exploring how the creative and technical components of a given project can and do work together, it’s been enlightening to learn about how these elements combine to create a performance aesthetic. That performance aesthetic is related to the experience of viewers and communities, but there’s one architecture firm that is taking these concepts to a whole new level.

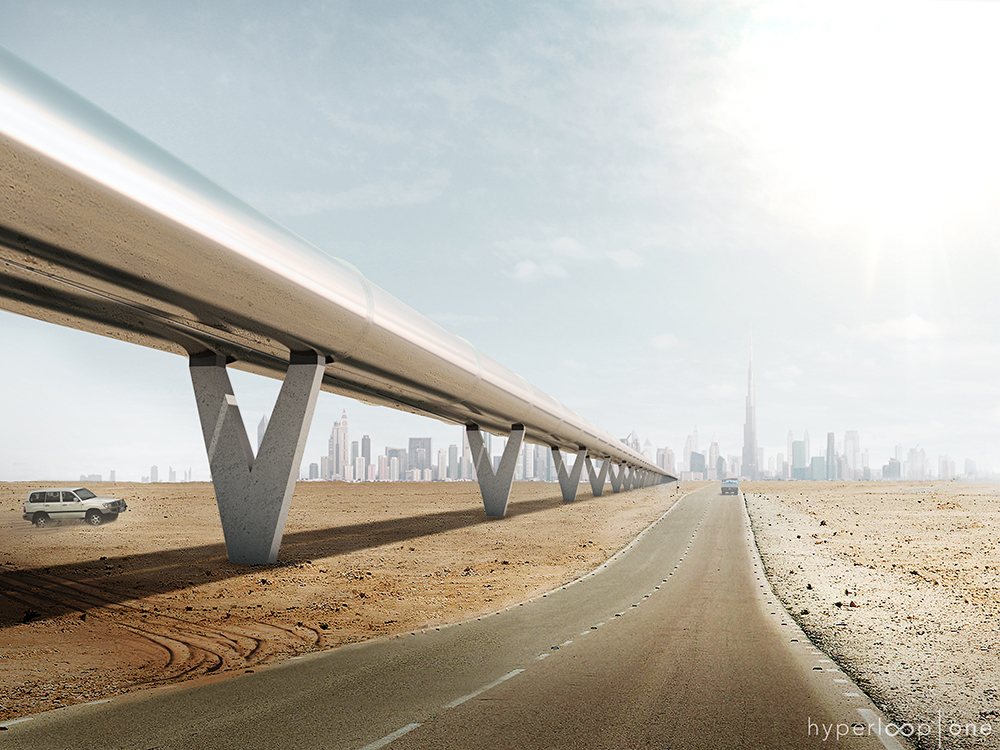

Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG) is a Copenhagen, New York and London based group of architects, designers, builders, and thinkers that are pushing the limits around what we think of when it comes to terms like “architecture”, “landscape design”, “urbanism” and plenty more. That redefinition can be seen in BIG projects ranging from the new NYPD 40th Precinct Building that is designed to strengthen the department’s commitment to community policing, to the Hyperloop One (pictured above), which combines collective commuting with individual freedom at an incredible speed. What does this redefinition mean to the communities that are being impacted by these projects though?

Kai-Uwe Bergmann

That is a concept BIG Partner Kai-Uwe Bergmann spoke about when he took the stage for a TEDx presentation. In it, Bergmann discussed what it means to curate space as opposed to doing architecture, and how BIG looks to find a new life for things that have been built for one purpose, but are no longer a fit for it. How these concepts work on a creative and technical level is of critical importance, and they’re worth considering in light of the way in which social infrastructure projects are impacting communities on a small and large scale.

Where Art Meets Architecture

In defining what social infrastructure projects are, Bergmann mentioned during the TEDx talk that the High Line in New York serves as a perfect example of one, since it is a park that has been created on an elevated section of a disused New York railway. Being able to think about how such spaces can be used and reused is a concept that certainly exists in the architecture world, but how it extends into and out from the art world is an important consideration.

“We think of architecture as a pragmatic art form,” Bergmann told AEC Next News. “You’re expressing an aesthetic vision, but you’re doing so with gravity, needing to protect from the elements, providing utility, services, etc. So what we’re creating is at its’ essence an artform, but it requires a bridge between the real world and the ephemeral world.”

Being able to consider how such space can be used is something that goes back to Bergmann’s first job out of school, where he worked as the first architect in Dale Chihuly’s studio. Though famous for his glassblowing, Chihuly was educated as an interior designer, and his attitude toward glass as a medium is very spatial. There are numerous art forms that use space in an interesting way, and that’s a concept which BIG has taken to a different level in many of their social infrastructure projects.

What it means to use that space on paper means something much different than it does in reality though, but it’s a topic that is never far from the mind of these professionals.

The Eleventh

BIG Implementation

In looking at the designs for BIG projects like the ‘The Eleventh’ and Shuishuis, it’s easy to wonder exactly how constructability logistics have been considered. Many BIG designs are able to combine ambition and practicality in an incredible way, but how are these details worked out as projects come together?

Shuishuis

“Implementation is a very important part,” Bergmann explained. “It is for any architect, but we often need to take a different approach around how something is actually built or constructed. That is one of the reasons we’ve decided to start the BIG Engineering Department. It’s been a way to look at how the building process happens, and that the more and better informed we are, the better we’re able to actually implement those visions.”

Approaching implementation at that level means the team at BIG is not basing their decisions off of someone else’s work. Because of that, they’re able to not only justify the moves they make, but to also move forward with ideas that others might not be able to implement. That redefinition has meant their approach to social infrastructure projects can come from a completely different place in terms of how creative and practical elements are realized.

These kinds of social infrastructure projects have traditionally been in the realm of engineers or landscape architects in terms of defining how space is used, and the push to consider all of these elements more holistically has enabled a systematic way of thinking for BIG. It’s gotten them to consider elements like how water systems and cue distribution systems, and how transportation systems all link with the buildings and the places within a city.

All of it stems from an attempt to use space in a different way, in both a creative and practical sense. It means that BIG doesn’t just consider what it might look like to design something like a playground, but to instead consider how that playground can impact the health of a community, and also be an important part of it.

NYPD 40th Precinct Building

Participatory Design

Social infrastructure projects like the High Line can impact an entire city, but these sorts of projects can be approached and realized on a neighborhood level as well. During his TEDx Talk, Bergmann talked about the various participatory design projects BIG has created, such as Superkilen, where the company worked directly with members of a community to create “parks for the people”. They’re spaces and objects that are based off of ideas and feedback that are provided from the community itself.

“I think it’s important to know that as designers, we don’t know everything, nor should we think that we do,” Bergmann said. “It’s a very collaborative process, and it requires a lot of different perspectives, more so from the population that uses the spaces once they’re complete. Because you’re thinking about what people need and want, you’re much more able to move the pendulum of design because people will support those things.”

That support is a key aspect of participatory design and success in social infrastructure projects. It’s a success that BIG itself has realized, where they populated a space in Copenhagen with 108 objects that were based on over 1,000 ideas that came from the public. Additionally, on The BIG U, instead of telling people what they needed for resiliency, they asked them what they were missing in New York, and many of them said green space and open space. So they designed a flood protection system that will provide protection for a tornado or hurricane, but otherwise functions as a park.

This kind of performance aesthetic is a direct result of firms like BIG taking a different approach to elements related to creativity and constructability. Doing so has meant social infrastructure projects of all sizes will redefine how communities consider the impact of these projects.