SmarterBetterCities uses 3D Maps to Involve Citizens in a Village Rebuilding Project

San Diego, Cal–We’re all aware by now that 3D-imaging technologies are indispensable for cataloguing and surveying damage after a natural disaster. But how can 3D help when you’re ready to start rebuilding? On Tuesday here at the Esri UC, Jan Halatsch, the CTO of Zurich-based company SmarterBetterCities , presented a project that shows just how necessary 3D maps are for that next step.

In the wake of the 2011 earthquake and subsequent tsunami, thousands of homes, many of them hundreds of years old, were destroyed in the Tohoku region of Japan. Working with local government and researchers at the University of Tsukuba, SmarterBetterCities began a project to plan the relocation of those who had lost their homes the reconstruction of their villages.

To create a model for the new villages, Halatsch said his company used archival data like photographs, maps, and scans of the pertinent areas. But that wasn’t enough–SmarterbetterCities and the Japanese researchers also needed human input. They hosted workshops where the relocating residents could see the 2D plans and help guide the process of rebuilding their villages by commenting on the plans as they developed. SmarterBetterCities then took that early input and created 3D models of the new villages that they used for all subsequent workshops.

Why was it important that models be presented to these people in 3D? “The problem with 2D maps,” Halatsch says, “is there is a lot of limitation. 2D maps are good for mapping specialists,” or other professionals who know what they actually mean. 3D maps, on the other hand, “just show you everything–if it’s bad, if it’s good, you can instantly tell. And therefore it shows everything that is important to the people who were actually inside the town.” To a non-specialist public (or, say, one of your clients), having information displayed in a language that is quick to read and easy to understand is crucial. Without it, they wouldn’t be able to participate in the process.

All comments were incorporated back into the model, which was then brought to another workshop, where another round of comments was incorporated into the model. This provided SmarterBetterCities and the other planners a fast, recursive process for planning the city. Given the very short time frame for the project, it also allowed them to include in their model a number of qualities from the original villages, qualities that are often lost in rebuilding processes like these. Halatsch lists, for instance, things like “social connections, like families living next door to each other,” the general feel of the village, and “things that, in the past, had been very fundamental, like iconic landscaping features.”

Because the 3D map allows the residents who attend these workshops to see and understand everything they needed to when reviewing the plans, they were able to tell the planners about specific features that were important to the character and history of the town. Halatsch lists, for instance, a tall tree that one family would use to find their way home in the winding streets of their village. Without 3D maps, the replacement villages would lack the details of the originals that had accumulated over hundreds of years. The new villages be a pale imitation at best.

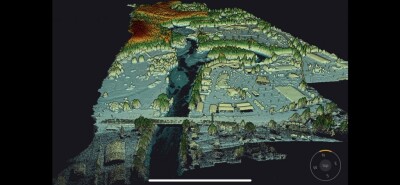

Image above is a screenshot from SmarterBetterCities’ 3D model for the project.

To see a demo the most current model, check SmarterBetterCities’ client page under Tohoku Reconstruction.