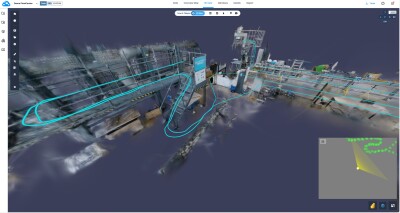

On June 15, 2008, Yolo County (California) Sheriff’s Deputy Tony Diaz was shot and killed as part of an altercation out on County Road 5 in Dunnigan. Last week, one of the last pieces of the prosecution’s case against Marco Topete, who’s charged with the killing, was provided by Craig Fries, of Precision Simulations, who used laser scanning to recreate the scene and reconstruct just how the shooting happened.

He used six of the seven trajectory marks that were on Diaz’s patrol car from shots fired, as well as the shell casing from the gun, an AR-15 assault rifle, to determine where the shooter was located.

According to Fries’ estimation and the work of forensic engineer Robert Cargill, who conducted test firing, the shooter was at the southwest corner of Jesse Gonzales’ house on CR-5 and shot through the porch toward Diaz’s vehicle. Cargill testified two weeks ago.

Fries agreed with Cargill’s previous opinion that Diaz was in a “crouched and bent position” when he was shot.

In addition, Fries said Diaz had his back turned when the shots began firing but turned to face the shooter with a bullet penetrating the top of his Kevlar vest, above his heart.

There’s no question this is a tragic event, but it’s possible it could provide yet another solid example of the way in which laser scanning can help police departments uncover and prove who committed a crime. As the technology becomes more accepted in courtrooms around the country, police are certainly keeping more criminals from remaining on the streets.

In this case, there was video evidence from the patrol car, but the video camera wasn’t facing in the direction from which the shots were fired. So Precision Simulations used the video evidence, along with bullet trajectories, to recreate the scene. Clearly, the Yolo Sheriff’s Department valued the work:

Under cross-examination, Fries said the Yolo County District Attorney’s Office paid him $10,000 for 200 hours of reconstruction work. He said if he had known how long it would take, he might have charged more.

Yep. Modeling isn’t cheap, especially modeling done for animation. However, if animation is one of the final pieces in proving the case, there’s no doubt the department will value it very highly.

One interesting piece in the article I’m going to look further into involves just how this video animation was presented. It’s a little confusing with the way the article is written, as there’s also a video confession being discussed, but this is the pair of sentences that caught my attention:

Gable said the judge reviewed the video reconstruction in chambers with testimony taking place in the court during pre-trial hearings.

“I’m a bit baffled with the people having no issue with the court viewing the simulation video in chambers,” he said.

Does this mean the jury didn’t see the reconstruction? Why not? Would the video be too prejudicial, but the testimony derived from it not? I’ll see what I can find out. I’ve heard from some reconstruction artists that they’ve often been told not to make the shooter in the reconstruction video look like the actual person being accused, even by the prosecution, because it makes it seem too damning. If the jury can actual watch a video of a guy who looks like the accused doing the shooting, maybe that puts too much reality in their head than is fair.

Hard to say where I come down on that. But it’s an interesting trend to watch. As these reconstructions get more realistic looking, and more accurate, how fair is it to create a video that will make it look like someone committed a crime, while the fact of that matter is still being debated in court?