I’ve been in this business long enough to see it change names a few times as it tries to find its way to ubiquity. I was first introduced to our discipline(s) as “high definition surveying.” As I learned about more non-Leica solutions, I started using the more generic “laser scanning.” A few years ago I started using “3D imaging,” as I thought that it was only a matter of time until sensors are powerful enough to allow for 3D scanning with ambient light and that the use of the laser would move to specialty applications. Then Autodesk entered the conversation and I started hearing a lot of folks using the term “reality capture.” Now Autodesk has moved to the term “reality computing” and we once again have to decide what to call what we do.

I will admit that I often move back and forth between these terms based upon my audience. However, rarely does a person fully understand a new concept by name alone. As a result, I am a big fan of analogies. As I tried to use one to explain reality computing, it occurred to me that for the first time I was describing data processing as opposed to just data capture. Once I made that leap it seemed better to simply use an example as opposed to an analogy. The problem was that I didn’t really have one that expressed the potential of the concept as opposed to the current state of affairs.

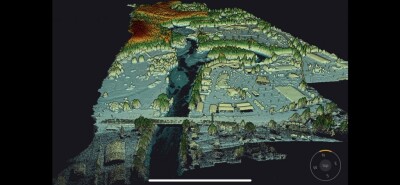

Then I heard a radio interview about archaeological finds of Paleolithic hunting sites beneath Lake Huron. For better images, see this article at mLIVE.com. While most of the interview is about the find, which is a couple of rock formations that were altered and used to funnel caribou into a trap, there was a small segment on why they chose to look in an area under 120ft of water for these structures. It turns out that they worked with Robert Reynolds and the Artificial Intelligence Lab at Wayne State University in order to predict caribou migratory routes in historic settings. They created a 3D environment that best represented the Paleolithic landscape, created caribou avatars that had known caribou traits, and ran the video game. This was used to determine the optimal migratory path, which in this case is a now-submerged land bridge under Lake Huron. They then used modern Eskimo hunting ethnographies to determine the best placement of hunting blinds given the predicted caribou migratory routes from the video game. They plotted these locations and then went for a dive to see if they were where they thought they should be.

To me, this was the real story! Putting known quantities in a virtual environment and letting it run. Dropping into that environment to experience a lost world. It’s easy to see this in the heritage market or as multimedia material for Discovery Channel, but the real power here comes from applying it to our time. I think we are on the edge of being able to simulate the entire lifecycle – including disasters, low probability weather events, dramatic reuse schemes, and more – of any environment on our planet, man-made or natural, existing or lost. Think about that for a minute. At some point in every project, perfection becomes the enemy of completion. Having the ability to simulate a multitude of variations could easily increase the level of productivity and the degree of perfection in our built environments. Maybe it’s getting the best orientation of a structure on a parcel of land. Perhaps it’s learning to move the exit doors a few feet in a particular direction to aid in evacuations. In the end it may be little things, but if history is any guide, we’ll find that some of our theories that are currently used in designs of all sorts are just that – theories. The sooner we move from basing our world on theory to reality, the better our reality will become.