A few weeks ago, Sean passed a couple of links my way regarding the questions surrounding the trademarking of point cloud data. He asked for my opinion and, after emerging from the rabbit hole nearly a month later, I’m still not sure exactly what my opinion is. However, I am sure that the questions brought forth are both thought-provoking and in need of consideration by anyone that works or plays in the reality capture space.

Let’s start where Sean dropped me in to this and see where it goes…

The post he sent me was “Why 3D Scans Aren’t Copyrightable” by Cory Doctorow. The post is basically a summation of the work of Michael Weinberg who is the General Counsel for Shapeways which is a company/community built around 3D printing and 3D design. I must admit that my first instinct was one of suspicion: Of course the attorney for a 3D printing company thinks that 3D scans are not copyrightable, it’s in his employer’s best interest! However, after taking the time to read his other papers, I do think that he is right–you can’t copyright a scan. However, getting around the rules that make him right are so easy that I’m not sure it will matter the way we think.

The post he sent me was “Why 3D Scans Aren’t Copyrightable” by Cory Doctorow. The post is basically a summation of the work of Michael Weinberg who is the General Counsel for Shapeways which is a company/community built around 3D printing and 3D design. I must admit that my first instinct was one of suspicion: Of course the attorney for a 3D printing company thinks that 3D scans are not copyrightable, it’s in his employer’s best interest! However, after taking the time to read his other papers, I do think that he is right–you can’t copyright a scan. However, getting around the rules that make him right are so easy that I’m not sure it will matter the way we think.

Let’s go a bit deeper by defining a few terms that we will need to use

- Physible: a dataset that is capable of being manufactured as a physical object using a 3D printer or DNC machine.

- Copyright: the exclusive legal right given to an originator or an assignee to print, publish, perform, film, or record literary, artistic, or musical material, and to authorize others to do the same.

- Patent: a government authority or license conferring a right or title for a set period, especially the sole right to exclude others from making, using, or selling an invention.

- Design Patent: a form of intellectual property protection which allows an inventor to protect the original shape or surface ornamentation of a useful manufactured article

- Trademark: a symbol, word, or words legally registered or established by use as representing a company or product

Clearing up Confusion

One of the most confusing aspects of this to the layperson is the common misuse of the terms “Patent” and “Copyright.” To further clarify, here is a comparison chart based on Weinberger’s work:

COPYRIGHT PATENT Covers artistic, creative works Covers useful articles Automatically protects a work upon fixation Must be applied for Work does not have to be new to society Work must be new to society Lasts for life of the author plus 70 years Last for 20 years Law assumes damages for infringement Must prove damages from infringement So, as you can see, patenting scan data seems to be right out because scan data is not “new to society” as a concept at this point. However, the idea of copyrighting scan data seems legitimate (at first) due to the fact that it is a data file you created—and we know from the music industry that companies can copyright files they created.

The difference, and the reason that music and movies are copyrightable, is because they are creative works. Scan data, on the other hand, is not created but recorded. “So are songs,” you might say. Yes, but a recording of a song is the recording of a creative work where as a scan of a building is not.

This is where it gets a bit confusing. The building was a creative work by an architect. The design plans for that structure are copyrightable. However, you can take a photograph of that building without breaking any copyright laws, and you can even copyright that image of the building if the image is deemed artistic in nature. Confused yet? It gets better… if I take my scan data (which can’t be copyrighted) and render an image with it, that “artistic” endeavor can be copyrighted.

This is where it gets a bit confusing. The building was a creative work by an architect. The design plans for that structure are copyrightable. However, you can take a photograph of that building without breaking any copyright laws, and you can even copyright that image of the building if the image is deemed artistic in nature. Confused yet? It gets better… if I take my scan data (which can’t be copyrighted) and render an image with it, that “artistic” endeavor can be copyrighted.Too Long, Didn’t Read?

Perhaps the best way to think of this is from an artist’s point of view. The point cloud is raw like the paint on a palette. You can copyright what you do with that paint but you can’t copyright the paint itself.

What That Means For Intellectual Property

Now, most of the current documentation on this topic is directed toward 3D printing. It’s easy to understand why. Currently, creators of objects can control the use and cost of an object by controlling the manufacturing of said object. The 3D printer and lower cost CNC tools hold the promise of changing that dynamic.

Since we saw the entertainment industry respond to the digital revolution with legal action, legal recourse seems the most logical approach here, too. However, there are some significant differences for those who are preparing to take on the maker community as if it were Napster 2.0.

An artist’s altered derivative of a 3D scan of… a mouse. Source: Plummer Fernandez

For one, many of the items in question–objects they might want to 3D scan and 3D print–are covered by patent as opposed to copyright protection. This means that, unlike the copyright infringement suits launched by the entertainment industry for music pirating, the patent owners have to prove that they were damaged by the infringement. (Unless you are printing a copy of an artistic sculpture, in which case it would be protected by copyright law.)

The other hurdle patent owners will face is the shorter term of the protection they are afforded. Patent protection only lasts for 20 years. (Only four more years and all you guys needing to print a replacement part for your Cyrax 2500 should be in the clear!) In contrast, copyright protection currently extends for the life of the author plus 70 years. I say “currently,” because this was not the case until 1998 when Senator Sonny Bono extended the term from 50 years to 70 years just before Disney lost Mickey Mouse to the public domain. They will be in the same position in less than two years and it would not surprise me a bit to see another attempt to extend the term.

Trademarks are another matter entirely. Simply put, you cannot legally reproduce a trademarked item. For instance, I can print a new grill for my Lexus but I can’t print the Lexus logo, as it is trademarked. If the original grill had the logo worked into the design then an exact copy would be trademark infringement.

…and that’s about as far as I can go before my questions outnumber my answers. While I feel comfortable with my (non-legal professional) opinions to this point, there are several outstanding issues that may impact this area in the near future:

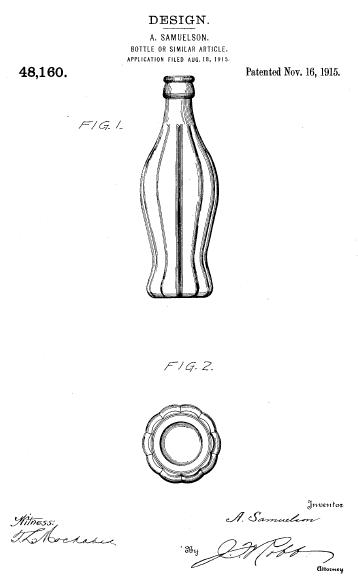

The Coca-Cola bottle is protected by a design patent, but if a designer makes a few tweaks, that protection disappears.

End User License Agreements (EULA) – These have used to restrict the rights of owners of software and are now being used for physical products as well. John Deere is the most famous example of that, but other manufacturers (such as GM) provided amicus briefs to support their case. This could be used to restrict an owner from making a physible of a portion of an object they bought.

- DMCA Extension – There is some talk that one way to address physibles would be to extend the Digital Millennium Copyright Act to include them. I think this would be the preferred route of those that hold large amounts of products that they fear losing the manufacturing control over.

- Iterative Design – How much does a design need to change to become “new”? Companies such as Autodesk have been pushing cloud-based iterative design tools for a few years now. While the idea and promise of usability is outstanding, I have to wonder about ownership issues. If I take someone else’s Revit model and use iterative design tools to alter different assets, at what point is it my design? What happens when two architects start with a flat roof and both put in the same parameters in the iterative design tool? My assumption is that they would both derive the same “original” design. How is that going to work out legally?

- Design Patent – This could be used to keep you from making an exact copy of something like the rear spoiler on a particular car. However, a few tweaks to the shape should get a maker around this issue.

I would love to end this with an overarching statement that provided clarity to this entire issue. Unfortunately, I simply do not think it is possible.

Conclusion

As of today, the moving of information from physical to digital and back to physical has superseded the intention of the framers of most intellectual law. From the point of view of someone working in the reality-capture space, I do not think it is worth the time or money necessary to try to use intellectual property laws to protect scan data. There are certain deliverable products that a derived from scan data that qualify, but most of them qualified before scanners existed, so that’s really nothing new. I’m afraid that the reality is that we are just going to have to watch this as the market unfolds.

Every other replicating system that I can think of (paper copier, paper scanner, MP3, etc.) pushed the legal limits a bit and was brought back into a slightly stricter use by case law. If you did not think your vote mattered before, here is reason to stay in tune with the officials we elect. They will undoubtedly be the ones to finally codify our rights in this area. Given most of the political talk this season I fear that we have a lot of work ahead of us simply trying to help them understand the issues involved.