It’s a truism that’s often thrown around our little industry, but it bears repeating: You really have to see 3D to “get it.” It’s a visual medium that doesn’t work well conceptually.

And, sometimes, 3D representations of reality are necessary for people to “get” other things.

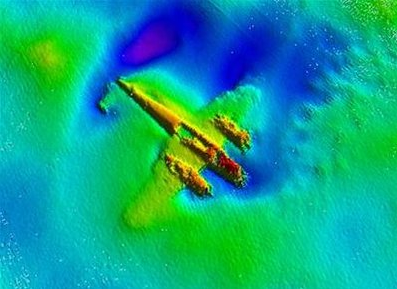

Take the case of the Dornier 17 RAF bomber that’s recently been uncovered, relatively intact, on the bottom of the English Channel. The thing is, people knew it was there. They have known for a while:

The plane came to rest upside-down in 50 feet of water and has become partially visible from time to time as the sands retreated before being buried again.

It’s a popular place for divers to check out, looking for a bit of treasure to take home. But, suddenly, people are all excited about it. Why? Because they’ve got 3D images of it, provided by a sonar survey undertaken by the Port of London Authority. And those 3D images say the plane is in pretty great shape:

“This aircraft is a unique aeroplane and it’s linked to an iconic event in British history, so its importance cannot be over-emphasized, nationally and internationally,” he said.

“It’s one of the most significant aeronautical finds of the century.”

So, some junk on the bottom of the English Channel is suddenly, as we say here in Maine, wicked important, and they’ll be raising money for the purpose of getting it off the bottom, where it’s been lying for 65+ years. That’s what 3D can do.

What else can 3D make extremely important and interesting? Where else can we apply this technology (however we’re capturing the data) to change the way the world looks at something?

.jpg.small.400x400.jpg)